Will work from home stick?

Welcome to Plugging the Gap (my email newsletter about Covid-19 and its economics). In case you don’t know me, I’m an economist and professor at the University of Toronto. I have written lots of books including, most recently, on Covid-19. You can follow me on Twitter (@joshgans) or subscribe to this email newsletter here.

An announcement

Before going on to today’s post, I just want to announce that the updated version of my book, The Pandemic Information Gap: The Brutal Economics of COVID-19 has now been published. In case you would like to purchase it, here are some links to help you find some outlets.

And remember for Christmas, nothing says “I care” more than giving your loved ones a book about Covid-19 and economics.

Now back to our scheduled program …

Today’s post is about working from home (something I have written about before). Specifically, with about half of us now working from home rather than somewhere else, an often asked question is: will it stick?

I have actually participated in a number of discussions where CEOs speculate on this issue. The views range from “we expect things to return to normal” to “we are now wondering whether we can sell our office real estate.” Here are some public examples:

“I don't see any positives. Not being able to get together in person, particularly internationally, is a pure negative.” (CEO Netflix)

“We’ve seen productivity drop in certain jobs and alienation go up in certain things. So we want to get back to work in a safe way.” (CEO JP Morgan Chase)

“We have adapted to work-from-home unbelievably well… We’ve learned that we can work remote, and we can now hire and manage a company remotely.” (CEO Rite Aid)

“Until recently, work happened in the office. We’ve always had some people remote, but they used the internet as a bridge to the office. This will reverse now. The future of the office is to act as an on-ramp to the same digital workplace that you can access from your #WFH setup.” (CEO Shopify)

“If you’d said three months ago that 90% of our employees will be working from home and the firm would be functioning fine, I’d say that is a test I’m not prepared to take because the downside of being wrong on that is massive.” (CEO Morgan Stanley)

“In all candor, it’s not like being together physically.…[But] I don’t believe that we’ll return to the way we were because we’ve found that there are some things that actually work really well virtually.” (CEO Apple)

The modal guess is on the likelihood that things will be different but it will be a rare industry that can say goodbye to the office forever. But can we get a clearer picture?

Jose Maria Barrero, Nick Bloom, and Steven Davis think so and have conducted a survey of 12,500 US workers to bolster their view. Here is what they find:

Our survey evidence says that 20 percent of all full workdays will be supplied from home after the pandemic ends, compared with just 5 percent before. Mechanisms behind the persistent shift to working from home include diminished stigma, better-than-expected experiences working from home, investments in physical and human capital that enable working from home, reluctance to return to pre-pandemic activities, and network effects that amplify other mechanisms.

A big part of their result is related to commuting. In particular, where does the commuting time go?

That is pretty interesting. Some of the time goes into work and other time gets returned to the workers. Previously, that time was all ‘wasted’ in a sense but, contrary to people’s perceptions, the waste was incurred by both workers and employers. This suggests that employers should be pretty happy about these developments. The survey, however, suggests otherwise.

Employers are dragging their feet on this one. But it does matter what type of job you are doing.

This makes sense. The ‘waste’ from commuting is highest for those who earn the most. And that waste is high for both parties precisely because of that.

One thing that has diminished is the stigma that comes from working from home.

This is an extraordinarily positive development. It bodes well for women in the workplace as well as for the ability to ‘renegotiate’ at-home outcomes that are more favourable to women.

All this adds up to expectations that change is afoot.

Not so fast

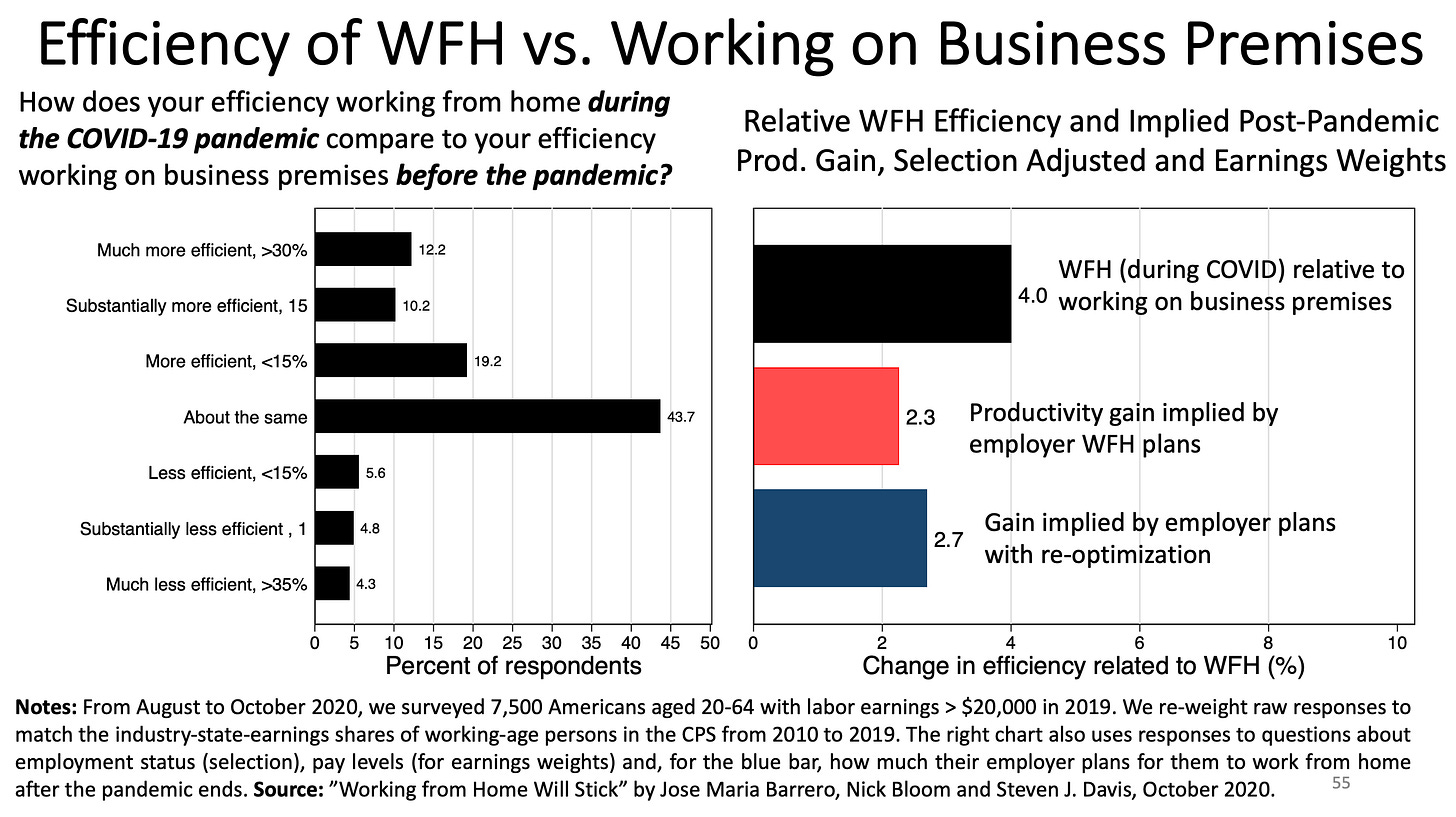

Earlier I asked whether we can “get a clearer picture” on the future of work from home. The survey attempts to do that but primarily looks at the immediate impacts and expectations formed today. That’s good but it might miss something. Here are current beliefs regarding performance:

But are those beliefs reliable? Are we missing something?

Tim Harford argues that we might be. He focusses on what we might be missing in terms of communication.

What gets less attention is the simple communication error. It is remarkable that activities for which face-to-face co-ordination seemed essential can be conducted from kitchen tables across the world. Yet eventually the cracks start to show: everything from missed emails causing missed meetings to yawning chasms of understanding about fundamental goals.

When we are distant, we push more to make communication more efficient. But there is a potential gain to having some latency in communication — saying more today in order to reap more tomorrow.

… a more insidious threat is the slow accumulation of what the psychologist James Reason calls “latent conditions”. In an industrial context, latent conditions might include an untidy pile of flammable oily rags in the corner of a workshop, a fire alarm that is out of batteries and a blocked fire escape. None of these latent conditions will cause trouble, until a stray cigarette causes a fatal fire.

For an organisation with an ambitious project to deliver, the flat batteries and the blocked fire escape are metaphorical. Colleagues working together on a project can find themselves labouring under very different assumptions about deliverables, budget, priorities and even who is handling which tasks.

The mismatch of beliefs can persist for a long time until a sudden and perhaps catastrophic moment of realisation. As the saying goes, it’s not the things you don’t know that cause trouble — it’s the things you do know that aren’t true.

A related issue is when some participants fear that a project is badly flawed, but there is no easy, informal way for them to pull a superior to one side and discreetly express their disquiet. One can’t help wondering if this summer’s bungling of grades for cancelled exam results in the UK would have been quite so shambolic if everyone concerned had regularly seen each other face to face.

The point is that we don’t really know what we are missing precisely because we are missing them. Eventually, that stuff will show up in the productivity numbers but right now we cannot be assured those numbers will capture long-term effects.

That said, this works both ways. To be sure, the forced experimentation to move to work from home has had immediate implications and removed some tacit and unstated productivity benefits from face to face interactions. But, at the same time, innovations that makeup or even make better the work from home situation are similarly yet to come. People will adapt and other ways of communicating will arise. What is certainly true, like much arising from Covid-19, it will be fodder for researchers for years to come.