Time to adjust your assessment

Going online means you have to assess students in a different way

Welcome to Plugging the Gap (my email newsletter about Covid-19 and its economics). In case you don’t know me, I’m an economist and professor at the University of Toronto. I have written lots of books including, most recently, on Covid-19. You can follow me on Twitter (@joshgans) or subscribe to this email newsletter here.

Today’s newsletter is not written by me (Joshua Gans) but instead is from Carl Bergstrom from the University of Washington who has been a major source of clear information during Covid-19 (and also co-author of a great book whose title I can’t mention here that you should all read).

Last Saturday, Carl posted a tweetstorm about how university instructors and other teachers are approaching assessment during Covid-19 and argued very convincingly that they should change their practices. This resonated to me as I have seen my own kids at university struggle with attempts by their professors to continue assessment as usual with various crazy behaviours including fixed time lengths for downloaded exams, increasing the volume of questions in exams to make sure it is hard enough, and requiring students to find a printer/scanner so they can submit hand-written exams. What follows has been reposted with permission.

From @CT_Bergstrom

A thread for my fellow college and university instructors, though high school teachers and students may be interested as well. Amidst the pandemic, we're all trying to adapt to giving and taking exams online.

The "simple" solution is to keep writing exams as we always have and use the multifarious tools of digital surveillance to reproduce the conditions of a supervised classroom exam.

But think for a moment about what this does. First:

Privacy

Software for online exams can require a student to scan their whole room before testing. Not everyone wants to reveal their home conditions. I know students who sit in their cars in a McDonald's parking lot, using the restaurant wifi, because they don't have their own wifi at home or, in some cases, a place to call home at all. These packages allow an instructor to watch a student from up close, over a webcam, for the entire duration of an exam without the student's knowledge. The potential creep factor on that goes right off the scale. They can penalize a student who interrupts their test-taking activity to turn away, to speak to someone else, to leave the room — assuming that the student is cheating, when more likely they are attending to child or parent or grandparent. They can monitor all internet traffic, take screenshots of the student's desktop, track the mouse around the screen, compare the face on the webcam with a scanned ID, even use the webcam for eye-tracking to make sure the student does not look in an unsanctioned direction. Supposedly they don't access pre-existing files on the computer unless those files are opened during the exam. Supposedly.

But these are proprietary technologies, not open source code, so who knows what they do.

You're asking students to install spyware, plain and simple.

Trust

Using one of these surveillance programs sends a signal to every student in your class that they can't be trusted. And then showing a lack of trust signals a lack of respect. I won't go into detail, but carefully consider the cost of that.

Hassle

While I have not verified the authenticity of these instructions for a math exam, they illustrate the level of detail that students would deal with when taking an exam on the higher security settings of these programs.

False positives

I've seen very little from the providers of this software about false positive rates. In my 20 years of teaching, I have accused students of cheating—but I've only done so in the face overwhelming evidence. Are you going to trust a software package that claims a student had unauthorized programs running? Think about the array of operating systems and background applications—virus checkers, backup software, indexing apps, etc. Would you do so w/o knowing the false positive rate? What if the software says the student’s eyes left the screen too often? Do you trust the face recognition and eye-tracking to have gotten that right? Has it been tested on all ethnic groups? Or, like all too much of facial recognition, was it trained mostly on white faces?

Diversity, equity and inclusion

Just about every ill effect of these exam surveillance packages falls harder on students of color, first-generation students, and students in other protected classes.

I'll explore just a few of the ways. Some tie into the factors above. Lower SES students may be less likely to have access to spaces (1) that they are comfortable allowing others to see and (2) where they can take the test in privacy without interruption—which may be necessary to avoid being accused of cheating. They may also be less likely to be running the up-to-date hardware and operating systems on which I suspect these surveillance programs will have been most thoroughly tested. Again, that puts these students at higher risk of being falsely accused. Non-traditional students (among others) may not have the luxury, during a pandemic, of setting aside all family responsibilities to avoid all interaction with others and to keep eyes solely on the allowed part of the computer screen. Again, putting them at higher risk. Signaling that students are not trusted may have a very different impact based on the student's background. A student who has always assumed he will go to college and feels that he belongs there may react differently from a first-gen student questioning her place in academia. The cost of falsely accusing a student of cheating may be very different as well. Someone with my privileged background might be able to shrug it off and say "man, that software is bullsh*t." Someone used to feeling like others question their right and ability to be there will have a very different response.

Even when the instructor does not directly accuse a student of cheating, but simply notes deviations from the required protocol ("you got up during the exam", "you had background apps running"), this can be traumatic. In college, I dealt with an anxiety disorder. Even if the teacher waved it off, having my test flagged for potential cheating by a software algorithm would have sent me into a spiral that could have ruined my mental health for a quarter or longer. In short, the false positives that these systems generate will amplify feelings of not belonging and non-inclusion on the part of precisely the students that we most want to be supporting in their academic careers. I see electronic surveillance for testing as a fundamental affront to the privacy and dignity of our students. At the same time, it is likely to disproportionately label students of color and other protected classes as cheaters—and when such accusations are made, they will disproportionate harm to students in those groups. If this past June you made a commitment to antiracism, consider whether there are racist consequences of electronic surveillance software for exam-taking, along the lines of those that I've laid out above — and then act accordingly. --- (deep breath) ---

So what can we do instead?

As I mentioned in the first tweet of this thread, writing our tests as before and using these software packages is the "simple" solution.

We don't have to do things that way.

We can take it upon ourselves to do the heavy lifting needed to provide fair and accurate assessment without disrespecting our students or denying their dignity.

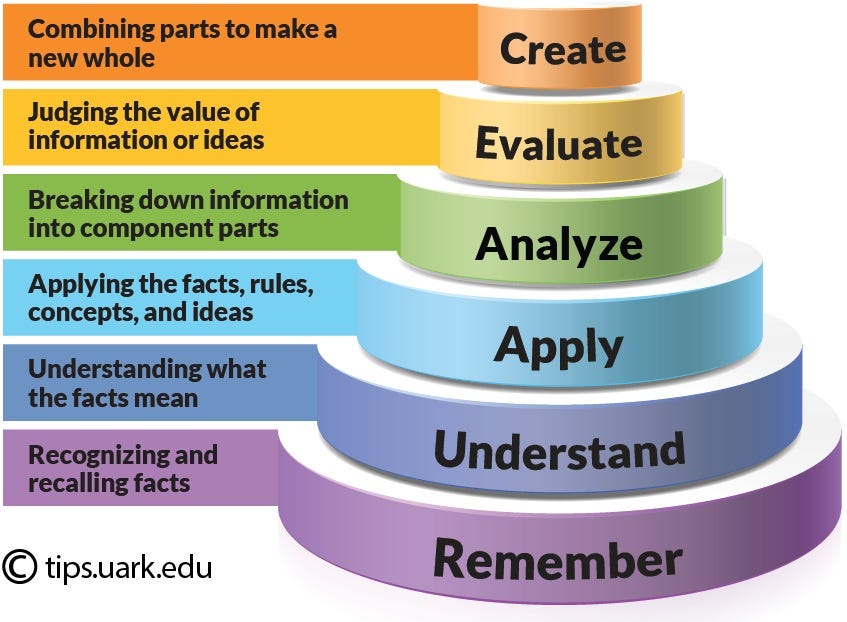

In the process, we may be able to improve both the quality of our assessment and the educational value of the assessment experience. We can transition from testing students at lower levels of Bloom's taxonomy (whatever you may think of its specifics, it captures the general notion I'm trying to convey), to test their ability to analyze, evaluate, and create.

Cheating — or, more positively, open books and open use of search engines and in the internet — is easy for exams that test your ability to remember facts and definitions, and probably useful for tests that get at understanding and application. That's fine. With a few very specific exceptions, if pre-pandemic we were primarily testing our students’ ability to remember, we were failing at our job — higher education should be about so much more and assessing only at that level does our students a deep injustice. Consider shifting the balance of courses away from examinations and toward other kinds of work. This can change to nature of the evaluation you are doing for the better and will be much appreciated to the many very good students who suffer from test anxiety. When you do give exams, write them to be open book, open note, open internet. It's not easy, but it's not that hard either once you get the hang of it. I find that this automatically pushes my test questions up onto the higher levels of Bloom's taxonomy. When you are asking your students to evaluate a scenario that you have developed yourself specifically for the exam, the internet will not provide answers—though it may support the process of deriving answers in a very positive way. When you ask your students to create their own scenario, or anecdote, or example, or narrative, or problem, or proof, or analysis, or argument, based on an innovative prompt, Google isn't going to have the answers but it may help them create deeper, better answers. You can think about it kind of like improvisational theatre. How do you know the troupe isn't running a rehearsed skit? They took the words "duck", "walnut", and "steam shovel" from the audience and crafted their story around those.

Writing test questions can be similar. For example, on in-person exams, I sometimes ask my students to write their own exam question that they think I should have asked, and provide an answer key.

If you do that with open internet, they can just search for one. But if you choose an event in yesterday's newspaper and specify that their question needs to relate to that, while bringing in something else that you specify, they are the ones who have to do the creating. The internet becomes a resource, not a source. These are the skills we should be evaluating our students on anyway.

Once they leave school, they'll have books, notes, internet...and they'll be asked to analyze, evaluate, and create.

Let's use this pandemic as a chance to restructure our own practices accordingly. Of course, all of this stuff is hard. I'm not getting it right yet, and a lot of the latter part of the thread is based on things I've learned the hard way, by screwing up. We don't have to get it perfect the first time around. This year is also a good year for lenience, patience, and empathy.

If your test ends up too easy, so be it. This fall, the world is too hard and a bit of balance would do everyone some good.

Thank you for reading this far, and good luck!

What did I miss?

So you want to achieve herd immunity

A preemptive warning to take care