Revisiting the number of doses

Can we get away with a single dose

Welcome to Plugging the Gap (my email newsletter about Covid-19 and its economics). In case you don’t know me, I’m an economist and professor at the University of Toronto. I have written lots of books including, most recently, on Covid-19. You can follow me on Twitter (@joshgans) or subscribe to this email newsletter here.

In November, when the news came that we would have a workable Covid-19 vaccine candidate (we now have 3+), I immediately wondered whether we needed 2 doses of the vaccine 3 or 4 weeks apart as the case may be. My rationale was severalfold: (i) it allows more people to have at least one dose of the vaccine quickly; (ii) it saves the accounting of who took what when; and (iii) with the logistics required, lifting any constraint on the system can be worthwhile. I was disabused of that notion by someone who knew about immunology. I, by contrast, knew nothing and was in awe of just how little I knew. In the end, the expectation is that one dose may not be enough to (a) protect people and (b) give long-lasting immunity.

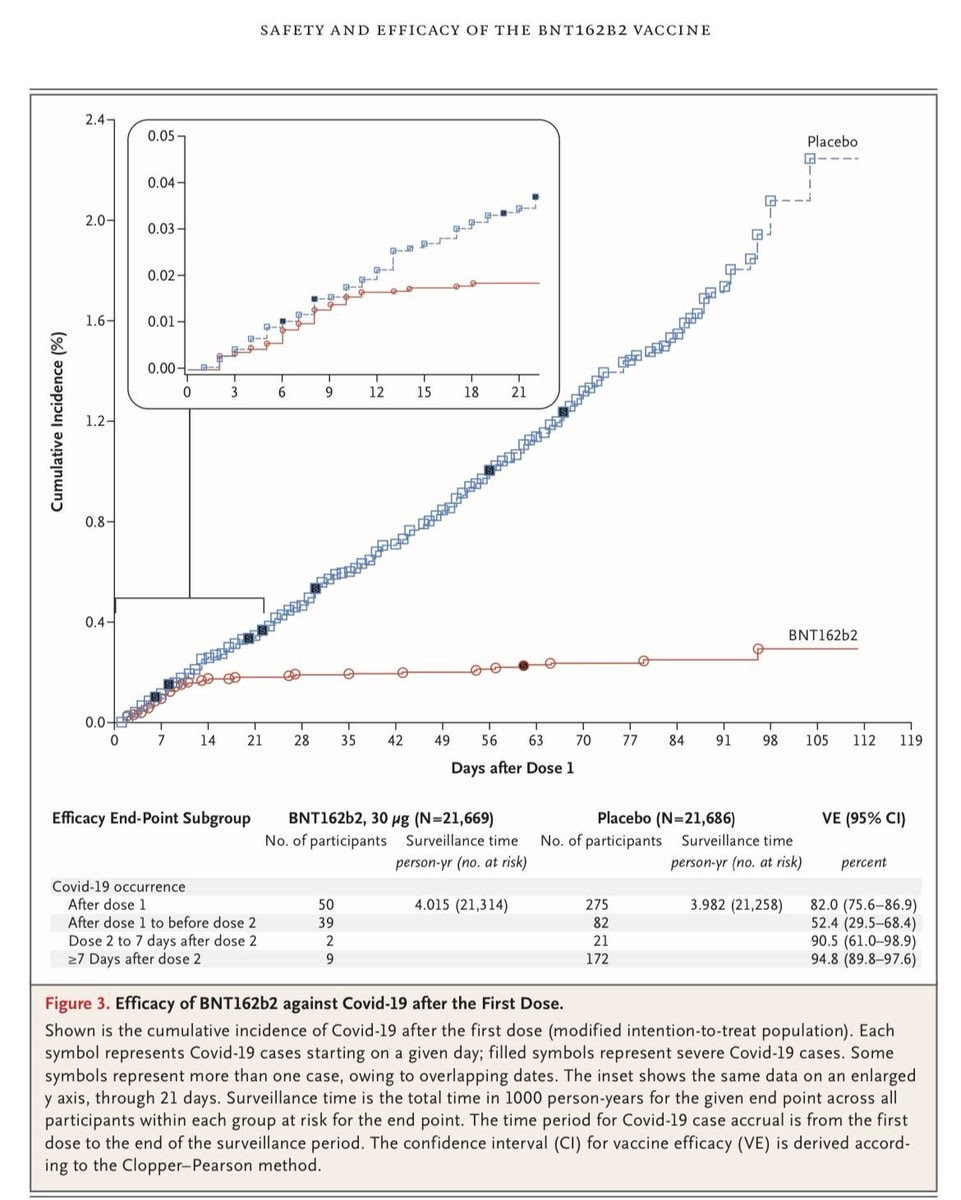

Last week, the issue finally reached Twitter. Zeynep Tufecki, who has been the most prophetic amateur epidemiologist in this pandemic, wondered why we were insisting on 2 doses. In other words, she was asking the question I had asked. But what spurred her on was details from the BioNTech/Pfizer study. In particular, this graph from this paper in the New England Journal of Medicine:

In the main graph, you can see that the effects of the vaccine are apparent after 14 days. That is, they are apparent after the first dose. Indeed, the data is shockingly presented. It looks as if Dose 1 gives 52% efficacy while both doses move to 95%. But that isn’t the case at all. First of all, there must have been people who had Covid-19 already when getting the vaccine. So the initial numbers are inflated. This can be seen with the inserted graph which shows the vaccine starting to take effect, as expected, about 14 days after the first dose. In other words, after 14 days, the first dose looks just as effective as the period after the second dose. Thus, contrary to what I had been told, it looked like the first dose did actually protect people. Real experts such as Bob Watcher and Michael Mina then chimed into to support considering the single-dose approach.

I should stress that we don’t know this for sure. We needed more information — something I noted back in November when discussing this:

That said, vaccine developers may test the immune reaction to first doses and work out of there is some latent immunity — perhaps from another past coronavirus. So it is possible that, for some people, if we can identify them, only one dose is needed. Suffice it to say, like everything to do with pandemic management, gathering information is the key to generating economic savings. (So apparently I can have insight into things I don’t know much about!)

I’ll come back to this below.

For the moment, let’s assume that the data is telling us what is — that is, that a single dose can be protective and so we should consider vaccinating as many people with one dose before giving people a second dose. To be sure, in the US, they are actually holding in reserve a dose for every person who receives the first dose. Thus, if in Month 1, you vaccinate 10 million people, you store 10 million second doses to come back to them in Month 2. Thus, by the end of Month 1, you have 10 million vaccinated.

What’s the alternative? You vaccinate 10 million in Month 1 and another 10 million in Month 2. Then you have the same number protected in Month 1 and double that by the end of Month 2. And that is assuming you can’t just give one dose to 20 million in Month 1. Do that and you have doubled your vaccinate rate.

This certainly seems compelling but there is a big wrinkle.

The Big Wrinkle

We don’t know how long the first dose gives you immunity. The theory is that it may just be temporary unless your body is given a second dose to create the right ‘immunity memory’ to last. There is reason to suppose that the second dose could come much later (as H1N1 immunity lasted for decades) but we just don't know. What if it only last 2 months.

If we had enough doses right now to vaccinate most of the population, that wouldn’t be a concern. We could do that and come back to it later — even if it took many months for the second doses to be manufactured.

But as we do not have enough doses, we have a problem. If I vaccinate 20 million in Months 1 and 2 with the idea of returning to them in a years time for the second dose, I double my rate of initial doses. However, as their immunity wanes, if the virus is still circulating, we could see a resurgence. Herd immunity requires having most of the population immune at the same time. If that is only a fraction — which it may be if the rollout takes the time we expect — then we never get to herd immunity this way.

Thus, have two issues. Pure health criteria argue for 2 doses to be on the safe side whereas economic and other circumstances suggest we do just one dose to accelerate vaccinations. It is a classic trade-off. But the second part, is that we don’t have a key piece of information to adjudicate this trade-off — how effective is one dose? We could have had this by now if some of the trial candidates had been given just one dose.

What should we do? There are no simple answers here. Any path forward requires value judgments that I do not feel I am equipped to make. We could just give some people one dose and measure how it goes. There are huge returns to finding that information. However, we run into the ethical problem that we do have an effective treatment that we believe is long-lasting and giving some just one dose (potentially unknowingly) pushes some risk on them.

How will people react

Getting people to get that second dose may become a challenge. If there is a belief that the first dose may be enough, then my expectation is that having people get the second one will become an issue. This isn’t for fear of the vaccine. It is just plain procrastination. Moreover, you will need a mighty fine IT and app notification system to just alert people and keep track of who has received that second dose. Wait too long and we may have to start all over again.

Of course, that flip side risk also emerges if people are told one dose will do and then that isn’t enough. The point here is that when there is the possibility of individual choice then the less information we have the more at risk we are of people making errors in exercising that choice. We don’t need that frustration right now.

The Big Take-A-Way

In the end, there is one message we have thus far: We are evaluating vaccines all wrong for the circumstances. Our procedures are to evaluate whether vaccines are safe and effective (in the sense of being protective). That generates incentives for developers to put their best foot forward on those aspects.

But in a crisis, we have other criteria. There is a desire to simplify the roll-out (can we get away with fewer doses) and to ensure that the pandemic is managed (does the vaccine also stop spreading). We do not evaluate either of these but both can be done with a properly constructed Phase 3 trial and ongoing testing as part of that trial. We have now lost months in terms of getting that information and, as a result, have tied ourselves to a business-as-usual, potentially slow model of trying to vaccinate entire populations. The lack of consideration here ranks as one of our biggest errors in managing this pandemic. I hope we learn from it before the next one.