The Covid-19 Grading Mess

With schools and Universities shut-down and on-line, grading students became a challenge and, in many places, the outcomes have been far from great.

Welcome to Plugging the Gap (my email newsletter about Covid-19 and its economics). In case you don’t know me, I’m an economist and professor at the University of Toronto. I have written lots of books including, most recently, on Covid-19. You can follow me on twitter (@joshgans) or subscribe to this email newsletter here.

Note: this week I am switching from a daily newsletter to just Monday, Wednesday and Friday.

Today’s post looks at the impact of Covid-19 on some aspects of education: namely, assessment. I review the UK’s terrible response with regard to 2020 University entrance exams and the naive use of a heavy-handed algorithm. There are ways of doing better.

As everyone knows, one of the first immediate impacts of Covid-19 was that students found themselves at home. The challenges were enormous. Thinking about how to continue education was hard enough and so many places set the issue of “how to assess” student learning aside. There were many reasons for this but my guess is no one had a strong interest in learning whether students were actually learning or not. Universities ended up giving professors substantial discretion to change assessment forms to anything so long as it didn’t involve physical requirements. They also wanted some grades, any grades to be turned in. The only other significant grading institutions, high schools where grades are used to determine University places, in many places, decided not to have much or any, additional assessment and rely on grades earlier in the year during the ‘normal times.’ At my youngest’s Toronto public school they told students that there would be assessment but that your grade could not fall below what you achieved prior to March. With only upside, economists will be pleased to know that the theory of moral hazard kicked in strongly and that was that.

With all that, you would think that it was hard to go massively wrong in your pandemic grading response. But then again, it is time to meet the United Kingdom. They undertook a solution that tried to ‘have it all’ with a one size fits all (well, almost all) policy, run by a machine that ensures that any unfairness that may have arisen earlier would be weeded out in a fair system. After all, what could be fairer than subjecting everyone to the same system?

Somewhere, someone must have stated a law: any system designed to generate fairness by treating everyone the same is destined to treat some people highly unfairly. If no one has said it feel free to call it ‘Gans’ Law.’ Regardless, let’s delve into our newest exhibit, the Ofqual algorithm.

The Ofqual Algorithm

High school assessment in the UK is governed by the UK government (given that they don’t have states, provinces and such). The entity charged with that is The Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation or Ofqual. You have got to love the Atwoodian dystopia type names that the British give to its government regulators; in Canada, it would get a peppy name like ‘Exams Canada’ or ‘Stressed Kids!’.

Anyhow, how did this all begin? Well with a political directive from the Education Secretary in March that “should ensure, as far as is possible, that qualification standards are maintained and the distribution of grades follows a similar profile to that in previous years.” Ofqual had its orders that the grade distribution should look the same.

The concern was this: the grade distribution doesn’t often look the same until students have sat their national qualifying exams — their A-levels. Put simply, there is a concern that school-based assessment tends to inflate grade expectations and that the national exams bring this back to, I guess, the ‘truth.’ But the national exams wouldn’t happen so students had a prediction of what their grades would be — something they had as a matter of course prior to those national exams — but no national exams. (Interestingly, note that Ofqual wasn’t worried about the educational value of these national qualifying exams — you know, students cramming for them as if their lives depended on it. They were just worried about the scoring component. This should give pay to the whole notion that education is just about signaling.)

Ofqual stepped into the mix by proposing to use an algorithm to adjust predicted grades and translate them into final grades while ensuring the distribution of grades was at its historic level. Now I certainly have nothing against a good statistical algorithm; after all, I co-authored a book on the subject of using them for the purposes of prediction. But the algorithm that Ofqual choose to use was not statistical. They didn’t want to leave anything to chance.

The resulting formula was simple; the details are here and I’ll spare you a deep dive into that. But it was easy to see why trouble was brewing. Not leaving anything to chance meant taking the historical distribution of final grades for each school at the subject level and then assigning grades for that school/subject based on the historic distribution. With a fixed number of each grade allocated, then each student would be ranked and then receive a grade purely based on their in-class rank. This handy video from the Financial Times explains all of this.

Suffice it to say, the problem with this was pretty apparent.

It wouldn’t be out of place in a maths A-level: suppose a class of 27 pupils is predicted to achieve 2.3% A* grades and 2.3% U grades; how many pupils should be given each grade? Show your working.

There are a few ways you could solve the problem. Each of the 27 pupils is 3.7% of the class, so maybe you give no one an A* or a U at all. After all, your class was effectively predicted to get less than one of each of those grades, and the only number of pupils less than one is zero.

Or you go the other way: 2.3% is more than “half” a pupil in that class, after all, and everyone knows you should round up in that case. So perhaps you should give one A* and one U.

Or you could pick the system that the exam regulator applied to calculate results on Thursday – now decried as shockingly unfair – and declare that no one should get the A* but someone should still get the U. U means unclassified, or in lay terms, a fail.

See what happened? In this class, every other year or so someone had failed their A-levels but the rounding that had to be done due to the fact you didn’t have half students lying around meant that they decided that someone had to fail! They rounded down because, you know, grade inflation. But what made for better news stories was at the other end of the distribution where the star student at a historically disadvantaged school was crushed.

Students with predicted A’s got C’s and thought it must have been a mistake. It was worse than that, it wasn’t a mistake. The algorithm was doing what it said it would do and people could foresee that was going to happen. The British government presumably was interested in this year looking like previous years. But the algorithm baked in harm to specific individuals and statistically, there was going to be someone harmed and, with certainty, they were doing to get all of the news attention. And not just little mistakes but life-changing ones like this and this one where a student expecting to get A’s and B’s got all D’s. This was completely predictable from the structure of the algorithm and, moreover, some small changes could have made it impossible for large changes between the predicted and actual grades to occur. After all, only a handful of students ended up with grades three or even two levels from their predicted. You could have checked and adjusted without breaking the system but they didn’t.

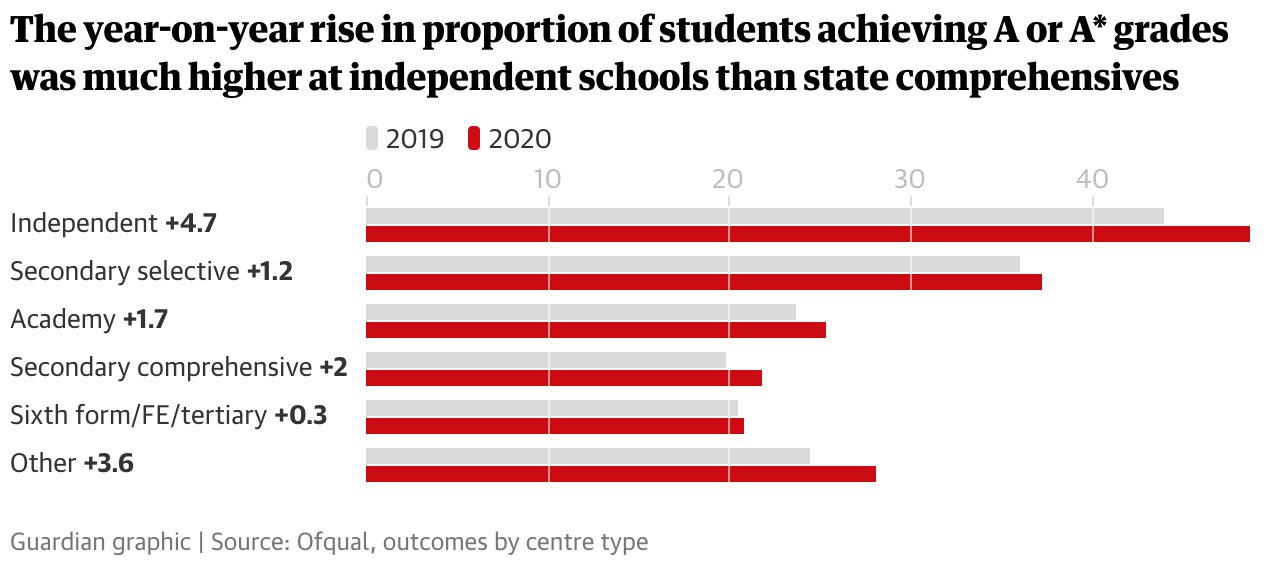

What’s worse is that all this effort to get the distribution looking the same didn’t happen either. This was equally predictable. Statistically, the algorithm was doomed to fail its own criteria. The problem was the distribution was based on historic averages. That meant that if you compared distributional outcomes in 2020 to 2019, there was no way there wasn’t going to be a difference. And the differences hit home with state-run schools doing worse than private ones. Given the party in power that was not a good look.

Why did it happen this way? Well, more disadvantaged schools were likely to have a higher grade variance within a subject than more privileged schools (you know, the ‘everyone at Harvard gets an A’ effect). But this year, the algorithm ensured that none of that would occur. So outliers that were expected and always occur did not. To be sure, you end up getting it most of the way there but you also prime it into a news and scandal making machine because you generate stories of clear inequity. (They also baked this in by exempting subjects and schools with very small numbers of students; take that those who doubt ‘Classical Greek’ is useful!)

The Right Way

Is the problem with reliance on algorithms? Tim Harford alluded that it may be:

The difficult question here was: could we give students the grades they would have earned in the exams? The easier substitute was: could we make the overall pattern of exam results this year look the same as usual? That’s not hard. An algorithm could mimic any historical pattern you like — or ensure equality (within the limits of arithmetic) based on gender or race. But note the substitution of the easy question for hard. It is impossible to give students the right grades for exams they never sat — one would have to be infatuated with algorithmic miracles not to realise that.

But infatuation with algorithmic miracles is not new. One of the first computer dating services was called Operation Match. In the mid-1960s, it promised that the computer would “scientifically find the right date for you”. In fact, it mostly matched people who lived near each other.An algorithm might try to predict romantic compatibility, but a wise couple would not marry on that basis without meeting. An algorithm might try to predict who will commit crime, and we might focus support on that basis. But I hope we will never dare to jail people for algorithmically predicted pre-crimes.

This point of view is understandable but I think it is too fatalistic. Here’s the thing: the UK system already provided students with predicted grades. But those grades were based on teacher assessment only. This system has been going on for years with teachers assessing student behavior and then national tests validating them or not. In other words, there is enough data to predict a student’s national test grade from characteristics of their school, subject, demographics, and how they individually performed prior to the national test. You can easily use machine learning or artificial intelligence as is called to provide a better prediction. This is something you should do if students are using predicted grades to set expectations of where they want to apply for University.

A key problem that arises in this is that of bias. One thing that may predict your final grade is whether you are part of a historically disadvantaged demographic. There is controversy on whether you should utilise an individual’s membership there in order to form predictions. Our gut reaction is that we should be blind to this. However, because the predictive algorithm isn’t blind to it, ignoring that characteristic can actually be harmful to someone who happens to be a member of a minority group.

The point is that this isn’t easy but whatever is happening at the moment is just sidestepping these issues and not dealing with them. That is surely worse.

Was Grade Inflation a Real Concern?

Coming up with better predictions is not something you would do on the fly during a crisis. If it had existed previously, it would be have been useful but it did not exist. So what should the UK government have done?

Ofqual’s starting premise was that teachers were better at ranking students than determining the level of their grades. Their desire was to adjust levels so that a student in 2020 didn’t receive a higher grade than an equivalent student in any other year. This is an odd criterion as it tries to maintain some sort of ‘gold standard’ logic to grading across years even though 2020 was surely an exception and could be explained away at any future time.

Instead, the real issue was the allocation of the current cohort of students to scarce University places. But here Ofqual’s premise that teachers can rank students suggests that the grades that they used could do a good job of allocating those scarce places. If grade inflation was just a function of a teacher’s bias then it is likely all teachers were equally biased which means that level of the grade doesn’t matter — the rank is what matters.

Note that it was precisely the ordering of students that Ofqual ended up using to allocate grades. So it trusted that. But that order would have maintained had the grades just been deflated a little across the board rather than deflated according to an algorithm that was non-neutral from the get-go! In other words, Ofqual came up with a bad way of dealing with essentially an issue of appearance.

The upshot of all of this is that the UK Government has had to reverse its position and rely on assessed grades anyhow. The problem is that the Universities now face having admitted some students who they wouldn’t have admitted and being forced to admit more students. In other words, the end result is the allocation result is unsolved.

That said, perhaps the Universities will be able to cope with more students especially if they are forced to be online for the foreseeable future.