Welcome to Plugging the Gap (my email newsletter about Covid-19 and its economics). In case you don’t know me, I’m an economist and professor at the University of Toronto. I have written lots of books including, most recently, on Covid-19. You can follow me on Twitter (@joshgans) or subscribe to this email newsletter here.

When I set out to write a book back on March 19, 2020, I felt like I would be “going it alone.” The idea was to take what we knew from economics and apply it to the current crisis. But very quickly, that mission changed. There was an incredible wealth of economics papers being produced that I was struggling to keep up. It turns out, many others had the idea of pivoting to Covid-19 and unlike my efforts they were conducting actual research into the issues. I was learning a ton and realised that part of my mission in the book was to synthesise that work and translate it for a wider audience.

Anyhow, for reasons I don’t quite understand, the LSE has been fascinated by these issues and has published some of my thoughts on that whole process.

Back in the day, I had a big interest in publishing in science and its impact. I even wrote a book (yes, I know, true to form or something).

What is really interesting is what has been happening for science in general. That is where a new paper by Yian Yin, Jian Gao, Ben Jones and Dashun Wang published in Science comes in. They were interested in whether recent work was have a faster impact on policy-making than before. We knew there was lots of it, but was it seemingly helpful? Here is what they did:

To explore COVID-19 science and policy, we harnessed a large-scale database, Overton, which records policy documents sourced globally from government agencies, think tanks, and IGOs. For each policy document, we then matched scientific references to our second dataset, Dimensions, a large-scale publication and citation database, offering a distinct opportunity to examine the role of science in the global policy response to COVID-19.

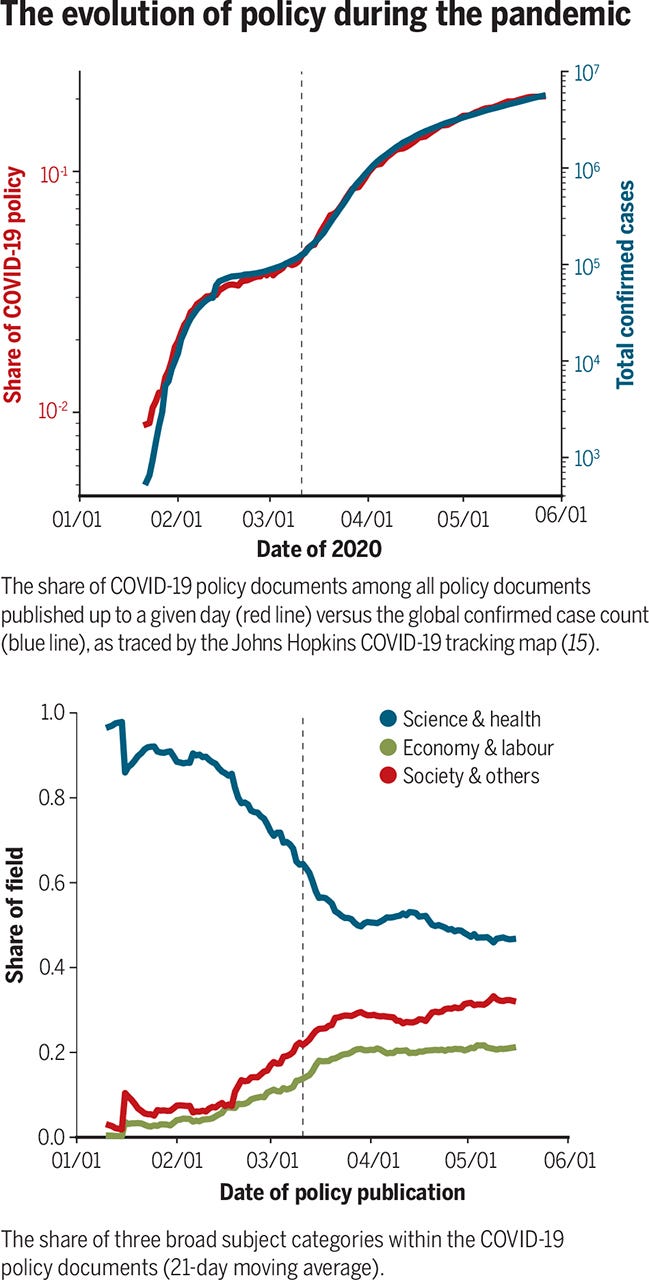

First of all, they find that policy-making was influenced heavily by Covid-19. Interestingly, it tracked the number of cases.

This is not that surprising but shares are very high — at least until May 2020, which is as far as the study goes.

More interesting, is the link between scientific research and policy-making. Here are the relevant graphs.

The first graph shows how, for Covid-19, recent research dominated in an unprecedented way. Interestingly, the Covid-19 papers that were cited by policy-makers also were the ones cited by other scientists. They write:

Together, these results show that despite the rapidly evolving nature of the pandemic, the policy and scientific frontier of COVID-19 are closely interlinked, with documents and articles that are directly along the policy-science interface (policy documents that cite science and the cited science itself ) being more impactful within their own domains.

But publication is slow right? Yes, if you want full-on peer review. But the research I was citing in my book had not been peer-reviewed, although I guess I was a peer reviewer for my purposes. But speed leads to mistakes and so we worry about that. It seems that policy-makers realised that. Pre-prints (that were not peer reviewed) were cited but not as much as papers published in journals like The Lancet.

There is also this tantalising analysis of policy document keywords that I’ll leave it to you to draw your own conclusions.

And which type of policy organisation was doing all the citations. Well, first, there were many more documents produced by government than by think tanks or by NGOs. But here are the citation probabilities.

The authors conclude from this …

Our final analysis examines the policy institutions that cite science, comparing national governments, think tanks, and intergovernmental organizations. We found that although government agencies produced the most COVID-19 policy documents among the three types of institutions (fig. S13), they are the least likely to cite science (fig S14).

By contrast, policy documents that are grounded in science are disproportionately produced by IGOs, especially by WHO (fig. S14). These differences in the use of science persist when we compare the indirect use of science (citing other policy documents that cite science), showing that IGOs again draw disproportionately more on the policy-science interface (fig. S14, inset). Many have argued that nations work best together through international institutions, especially in a crisis such as COVID-19 (11). These results suggest a key role of WHO and other IGOs in the global policy response to COVID-19, acting as central conduits that link policy to science.

My suspicion is that this piece of research, while interesting, is really not at the heart of the issue. What happened beyond May 2020 and over the next year will really show us the role science played in all of this. But we do have to actually wait for that.