The US Copyright Office is Anti-Prompt

Their new guidance on what AI-generated content is copyprotected neglects what current (and future) AI does and what is human insight

For regular readers, I do have lots of interesting stuff to write about regarding AI, but haven’t had a moment to do them justice. And I didn’t intend to write now about less interesting stuff like copyright and AI but the US Copyright Office put out a report yesterday that has sucked me right in. It is about what is protected by copyright when authors use AI to help them author. Bottom line: I don’t care much for their guidance.

A bit of background. I was involved a year or so ago with a group of economists advising the US Copyright Office on how to deal with AI at many levels. Our report came out last month, and I contributed substantially to the chapter on the copyright treatment of inputs to AI models. (I have written about that previously here, here, and here and wrote a paper now forthcoming in the Journal of Law and Economics). At the time, I have to admit that I disagreed with my fellow economists on what might be protected by copyright when people used AI tools, but it wasn’t my main focus.

The US Copyright Office has now put out its report on what is protected. Let me quote the highlights:

Questions of copyrightability and AI can be resolved pursuant to existing law,

without the need for legislative change.

The use of AI tools to assist rather than stand in for human creativity does not affect the availability of copyright protection for the output.

Copyright protects the original expression in a work created by a human author,

even if the work also includes AI-generated material.

Copyright does not extend to purely AI-generated material, or material where there is insufficient human control over the expressive elements.

Whether human contributions to AI-generated outputs are sufficient to constitute

authorship must be analyzed on a case-by-case basis.

Based on the functioning of current generally available technology, prompts do not alone provide sufficient control.

Human authors are entitled to copyright in their works of authorship that are

perceptible in AI-generated outputs, as well as the creative selection, coordination, or arrangement of material in the outputs, or creative modifications of the outputs.

The case has not been made for additional copyright or sui generis protection for AI-generated content.

The first thing here is that you need to have a human author to have copyright protection. I wrote about this previously. I don’t have my own strong position on this, although I am sad for the monkeys, but I am not sure whether AIs will starve without copyright.

The interesting issue that takes much of the report is a matter of degree. People will use AI to help them create creative works. The Copyright Office says that 100 percent AI-created content is not protected and that 100 percent human-created content is protected also, if you can neatly separate the two, then even better. But where do you draw the line?

This is another thing I have written about. I argued that there was really no such thing as pure 100% AI-created content, and so, for all practical purposes, so long as a human is claiming authorship, we should grant copyright protection.

Trying to draw some line between AI and humans with the current technology opens up a massive can of worms. There is literally no piece of digital work these days that does not have some AI element to it, and some of these mix and blur the lines in terms of what is creative and what is not. Here are some examples:

A music artist uses AI to denoise a track or to add an instrument or beat to a track or to just get a composition started.

A photographer uses Photoshop or takes pictures with an iPhone that already uses AI to focus the image and to sort a burst of images into one that is appropriate.

A writer uses AI to prompt for some dialogue when stuck at some point or to suggest a frame for writing a story. For example, this.

Put simply, AI is a tool like a camera or a typewriter or, for that matter, an autotune. Even if the work would have zero value sans the use of that tool, that does not mean the work was caused by the tool. The fact that it requires a human — the claimed human as the author of the work — to cause the entire thing to be generated is surely the fundamental component of authorship. Any blurring of the lines will lead to chaos and requires a view of the technology’s independence that makes no sense.

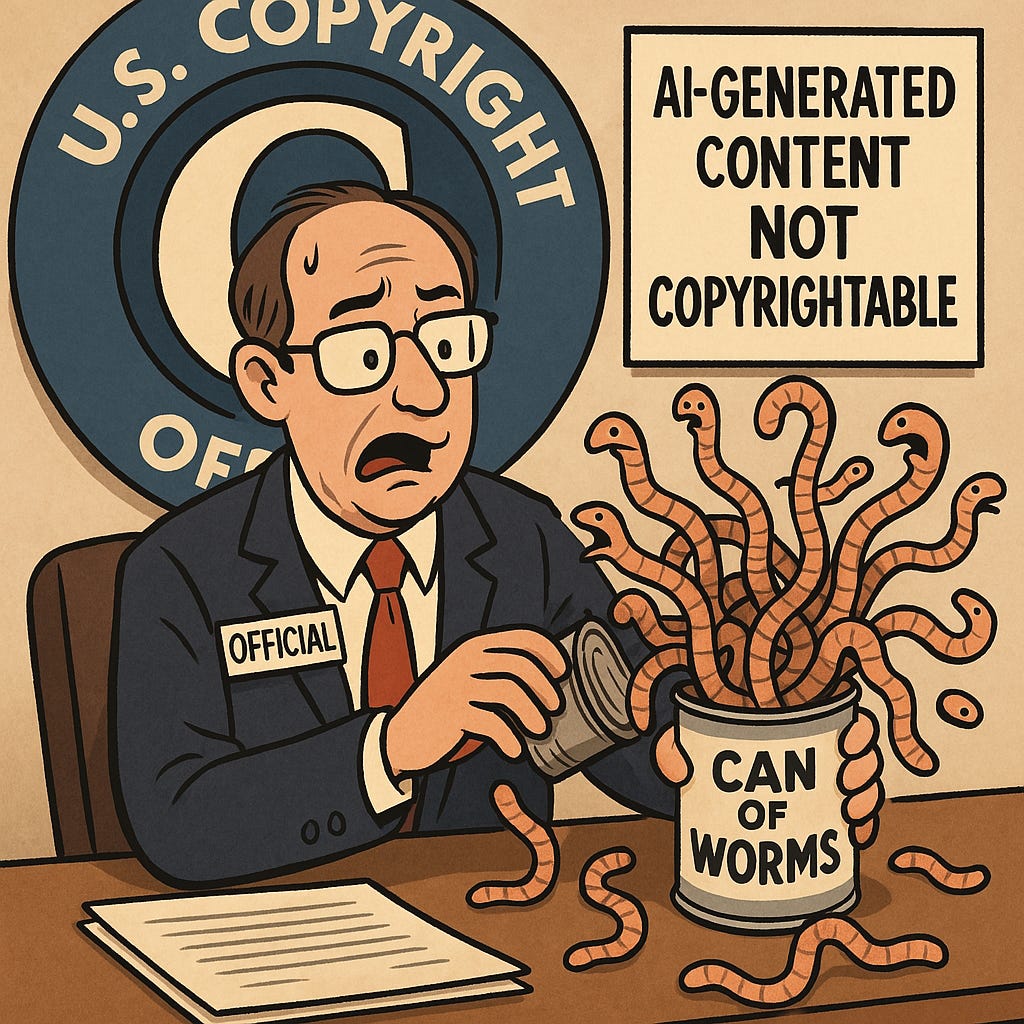

Suffice it to say, the US Copyright Office advocates opening the can of worms.

The War on Prompts

The Copyright Office’s report is very noticeable in its discussion of prompts that are the main way we interact with Generative AI and, let’s face it, the tools that will generate the biggest creative issues with respect to copyright. Here is what they identify about what prompts do:

The issue, fundamentally, is that when a user prompts an AI, the user does not quite know what they are going to get, why they get it and whether they can get the same thing again. These things are true although the last one is not necessarily true — that is, you can change the temperature of AI so that it does return the same response again and again.

When I wrote the following prompt to generate the picture above:

Generate an image showing an official at the US Copyright Office opening up a can of worms by arguing that some content generated with the help of AI is not subject to copyright protection. Make it interesting and a little amusing but very clear on what is going on.

I didn’t know what was going to come out. But what is clear from the Copyright Office is that if I tried to copyright that image, they would deem it unprotected, although I may be able to claim protection over the wording of the prompt. Here’s what they say:

The Office concludes that, given current generally available technology, prompts alone do not provide sufficient human control to make users of an AI system the authors of the output. Prompts essentially function as instructions that convey unprotectible ideas. While highly detailed prompts could contain the user’s desired expressive elements, at present they do not control how the AI system processes them in generating the output.

I’ll say this: at least it’s clear.

But is it correct? Let’s think about my prompt above. It didn’t come from nowhere. It came because I was writing this newsletter and looking for an image to capture attention and improve readership. I was also trying to be funny. I can’t say I spent lots of time on that prompt, but I can say it came from me, and the broad idea was mine. Is it of value? Who knows? But if someone took it and made T-shirts out of it without my permission, I’d be as upset as if they did that with the text of this newsletter.

On this, noted legal scholars agree:

Professors Pamela Samuelson, Christopher Jon Sprigman, and Matthew Sag stated that “[s]ophisticated prompts that specify details of an image should be sufficient to meet the [human authorship] requirement,” and that “[a] person who instructs a Generative AI with enough detail, such that model output reflects that person’s original conception of the work, should be regarded as the author of the resulting work.” Another commenter asserted that, with detailed prompts, users “can achieve remarkable control over the expressive elements of the work, such as lighting, pose, style, expressions, and setting.”

But the Copyright Office instead agreed with others:

In contrast, the Authors Guild argued that the unpredictability of the prompt-to-output generation process may make it “difficult to show that there was sufficient control and consequently a sufficient closeness between ‘conception and execution.’” Others agreed. Adobe, for instance, stated that “[w]hen you submit a prompt (or idea), you then receive an output based solely on the AI’s interpretation of that prompt,” and the “AI’s expression of [that] idea is not copyrightable.”

And don’t think that working on prompts through an on-going conversation will help either. The Copyright Office is unmoved:

Repeatedly revising prompts does not change this analysis or provide a sufficient basis for claiming copyright in the output. First, the time, expense, or effort involved in creating a work by revising prompts is irrelevant, as copyright protects original authorship, not hard work or “sweat of the brow.” Second, inputting a revised prompt does not appear to be materially different in operation from inputting a single prompt. By revising and submitting prompts multiple times, the user is “re-rolling” the dice, causing the system to generate more outputs from which to select, but not altering the degree of control over the process. No matter how many times a prompt is revised and resubmitted, the final output reflects the user’s acceptance of the AI system’s interpretation, rather than authorship of the expression it contains.

They go on:

Some commenters drew analogies to a Jackson Pollock painting or to nature photography taken with a stationary camera, which may be eligible for copyright protection even if the author does not control where paint may hit the canvas or when a wild animal may step into the frame. However, these works differ from AI-generated materials in that the human author is principally responsible for the execution of the idea and the determination of the expressive elements in the resulting work. Jackson Pollock’s process of creation did not end with his vision of a work. He controlled the choice of colors, number of layers, depth of texture, placement of each addition to the overall composition—and used his own body movements to execute each of these choices. In the case of a nature photograph, any copyright protection is based primarily on the angle, location, speed, and exposure chosen by the photographer in setting up the camera, and possibly post-production editing of the footage. As one commenter explained, “some element of randomness does not eliminate authorship,” but “the putative author must be able to constrain or channel the program’s processing of the source material.” The issue is the degree of human control, rather than the predictability of the outcome.

Well, this starts to seem quite crazy. No one is crafting a camera shot without help. What about autofocus? And how does control make sense? Consider these photos that won comedy wildlife awards, even though what makes them funny was surely just luck and not human control by any stretch. One of these days, an AI is just going to generate something funny, but the person who wrote the prompt and then told others about the output would not be protected, whereas if they had been taking pictures and something happened, they would. The inconsistency makes no sense to me.

Some Economics

To me, engaging with AIs to produce something feels like work and feels like my work. I don’t see the difference between using that and a paintbrush. But AI is a new technology so we have to consider whether it changes the fundamental economic rationale for copyright protection.

Here’s that rationale. Copyright law wants to promote the use or consumption of creative works and also their supply. Those goals aren’t always aligned. If you want to promote use, have no copyright protection and anyone can use the work. But, in doing so, if creating those works is costly, people may not create them in which case making their use freely available is of no consequence since the work doesn’t exist. Thus, we protect works but limit that protection in various ways, including how much of a work can be used, its purpose (e.g., fair use exemptions) and the duration of protection, which may change if Walt Disney is brought back to life.

What does AI do? It dramatically reduces the costs of producing creative works. Now, if you are a current producer with skills based on old technology, that may not be great news (I’m looking at you, Authors’ Guild), but that is just competition and, in principle, not what copyright is about protecting you from. But that cost does mean something. As Joel Waldfogel has pointed out, surely the degree of protection does not have to be as high when AI is available, which is true economically. But also implies that we should have different copyright protections based on what and how something is produced and when. This is not something I think we do.

Let’s hit this from the other direction. What does the Copyright Office’s very clear anti-prompting stance mean? I’m going to leave aside the whole “how do we prove something was just prompted” issue, as my issue here is with having to prove it at all, and so that is a cost to the Copyright Office’s side of the ledger. Instead, what does it mean to people’s incentive to prompt? To the extent that involves work, insight, judgment, intention and the like, the Copyright Office is basically arguing that it is for nought if you want to take that output and prevent people from just copying it. The fact that there was some randomness in the process is surely beside the point. Based on the pure economic activity of creativity, there does not appear to be anything special about prompting as opposed to writing, painting, sculpting, editing or pressing a shutter button. The black box nature and randomness are not unique to prompting. They are not unique to AI. They are tools of the trade used in creativity and are no more explainable than whatever is going on in our heads when we do stuff.

In the end, the Copyright Office is saying: we don’t want what prompting is getting us. Even if you are using AI to generate hundreds of options and then promote just one, the Copyright Office is saying “that’s on you.” But these are clearly potentially valuable activities that would be undermined if anyone could copy.

The Simple Path Forward

The path forward is obvious. AI is a tool like a paintbrush. People using it as a tool to help create works that they claim to have authored should be allowed full copyright protection consistent with past law. I agree there is no need to change the law. And right at the moment, we can stick with human authorship. But to claim there is something special about the AI technology that changes that stance is folly. Here’s hoping the courts don’t follow the Copyright Office’s guidance this time around.