The Triumph of Economists

Macroeconomists in government came to the right answer, without a playbook, and saved us

Welcome to Plugging the Gap (my email newsletter about Covid-19 and its economics). In case you don’t know me, I’m an economist and professor at the University of Toronto. I have written lots of books including, most recently, on Covid-19. You can follow me on Twitter (@joshgans) or subscribe to this email newsletter here. (I am also part of the CDL Rapid Screening Consortium. The views expressed here are my own and should not be taken as representing organisations I work for.)

It has been a while since I posted which is something you should take as good news. It means things are calming down even if they are far from over. But two pieces — one by Marc Andreessen and another by Noah Smith — appeared this week that motivated me to write about something good that happened that has received little to no attention thusfar: economists in government did their job in March and April 2020 and, in so doing, demonstrated economics’ greatest triumph: avoiding what could easily have been an economic and societal collapse. And what’s more, they did it based on skill rather than utilising some existing playbook.

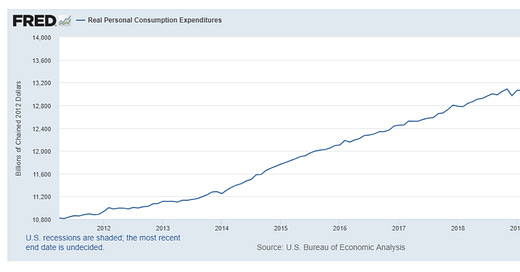

Here is the graph of triumph (from Noah Smith):

This shows US personal consumption expenditures. Its dual is this:

Unemployment is still high but given the nature of the disruption, it is much lower than expected and recovering. The picture is the same around the world. Faced with an unprecedented shock to demand and supply, economies could wear it and bounce back. The question I want to address is: who should get the credit?

Andreessen starts the ball rolling:

By far the scariest non-health implication of COVID was the simultaneous powering down of much of the supply (producer) and demand (consumer) sides of the economy at the start of lockdown. The prospect of a second Great Depression was very real, as reflected in the stock market collapse of early 2020. But then, a miracle happened — a technological miracle. Much of the economy kept operating, and in fact many parts of the economy started operating even better under lockdown than before. The primary credit for this goes to the American worker, but almost as much credit is due to the technology that made this miracle possible.

Ignore the US-centric nature of this statement, the credit is actually divided. Andreessen first points out how knowledge workers could work from home.

The most positively shocking development was that virtually all knowledge work in the economy simply kept going. Of course, companies were forced to shut down physical production facilities such as car factories, and frontline workers bore the brunt of in person exposure to COVID throughout the pandemic. But consider this: Not a single significant company engaged in service provision — whether banking, insurance, communications, media, healthcare, you name it — had any downtime at all. Every knowledge worker went home, fired up their laptops, jumped on Slack and Zoom and Gmail and Github, and kept on going. I must have talked to a hundred CEOs through that initial period, and they were uniformly shocked at how well remote work worked, right from the start.

And it is true. People could just work from home — about a third could — and, at least in the short-term, that kept things going. The same was true for all manner of life including education and entertainment. The Internet saved us. Indeed, Andreessen actually spends little time on workers per se. Let’s remember that WFH was no picnic for women with younger children that can make you wonder whether continuing work expectations helped. More critically, Andreessen does not acknowledge that it was people, not working from home, but getting out there, that made it possible for the physical needs of home-workers to be addressed. People do not live or work by bits alone. The Internet could not have saved us without the resistance of the ‘real’ economy. And those jobs were harder than before.

What stopped a major economic calamity, however, was how we dealt with the 20 - 30% of the workforce that suddenly had no role during lockdowns. It was as if some of the most significant employment sectors, retail, travel and entertainment, were wiped from the face of the Earth. Everyone employed there would no longer be able to consume and pay off loans and mortgages. Put that scenario in any economics exam and the consensus answer was that we were doomed. Indeed, almost all pandemic scenarios that I saw written before this one saw economic collapse as inevitable.

But it wasn’t. One of the first chapters I wrote for my book back in March 2020 was entitled “This Time it Really is Different.” The idea was that this was no ordinary recession. Nothing had been destroyed. Life had just been stopped. The problem was that payments had been stopped too. But there was no reason we had to do that last part. Keep the payments going and we could just restart where we left off when the pandemic was under control. The answer was surely obvious: spend big to keep payments going.

When I wrote this, I looked for past discussions and research on this idea and came up short. There was nothing there even though it seemed obvious to me. What is most extraordinary is that it was obvious to virtually all economists — particularly, those in government. Each of them came to the same conclusion. As a result of this amazing consensus, action was taken and taken immediately. All over the world programs were initiated to keep payments flowing or pause the consequences of non-payment. Subsidies were given to workers in some cases and businesses in others. Unemployment benefits were expended. And there were moratoriums on evictions due to non-payment of mortgages or rents. What is more, this worked. Indeed, if we haven’t fully recovered it is because we were too slow dealing with the pandemic itself. But the clear conclusion is that this time it really was different. Economists and economics did their job. And not me. I was just writing. But the economists who were in government and were persuasive and bold in their approaches.

Now there are wrinkles. There always are. How much needed to be done versus how much was actually done were likely not in balance. In many cases, payments were made to those who didn’t need it and so we have some unfairness and, in some situations, and this was surely to be expected, outright fraud. What is more, there will be consequences we are yet to feel from these interventions. That will take some of the shine off the achievement.

But for the moment, I want to acknowledge those economists who did their job right. It is a triumph of the system — perhaps its greatest ever triumph to date. It is a story that has been ignored because there have been more pressing matters. But there is a story there of what could have been and why it didn’t happen. I hope someone who is far more objective than I am will choose to write it.