Welcome to Plugging the Gap (my email newsletter about Covid-19 and its economics). In case you don’t know me, I’m an economist and professor at the University of Toronto. I have written lots of books including, most recently, on Covid-19. You can follow me on Twitter (@joshgans) or subscribe to this email newsletter here. (I am also part of the CDL Rapid Screening Consortium. The views expressed here are my own and should not be taken as representing organisations I work for.)

First of all, thanks to all the well-wishers out there on my Covid. I have to say I feel embarrassed because from my perspective I’m being wished well out of a modest cold rather than a deadly virus. My entire household is now down with it and we are pining for genetic testing to understand whether I was patient zero or not. Apparently, there is a great desire to assign or deflect blame, information that would actually help no one.

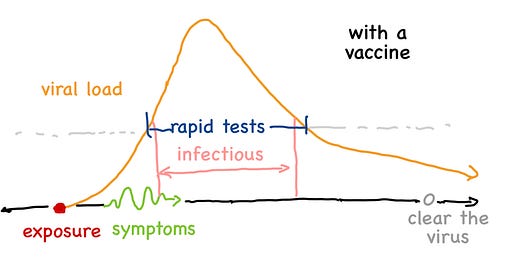

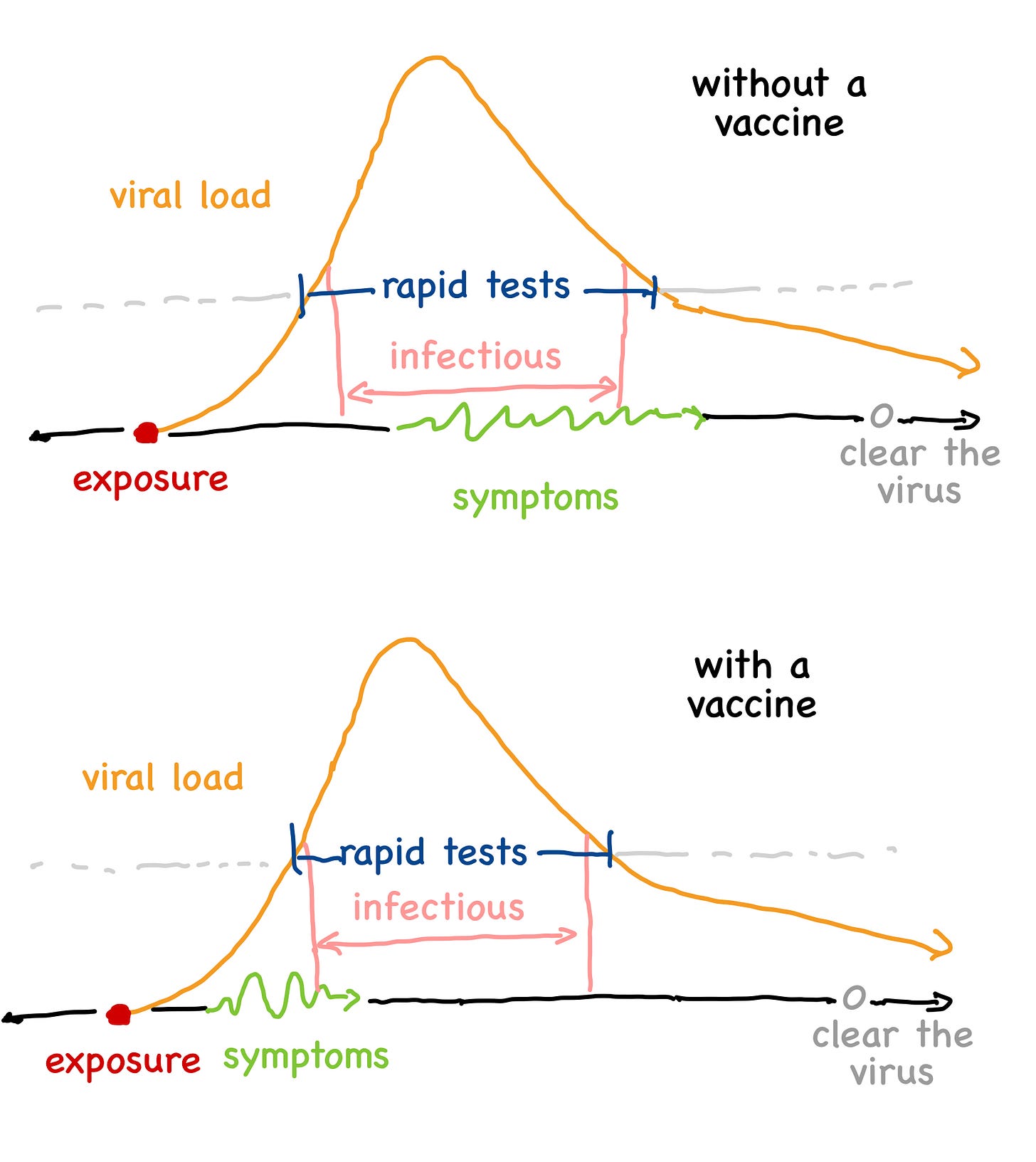

As I explained in yesterday’s post, we are now in a different phase of Covid for most people. James Cham adjusted the NYT graphs on Covid to summarise my argument. Here I do some more adjustments to enrich that picture.

I’m not quite the NYT graphics department but this will do. You will see here that with a vaccine (and potentially prior infection), what shifts in these diagrams is only the onset and duration of symptoms. I also adjusted the amplitude of the green symptoms line for severity. You’ll notice that you could be infectious without a vaccine prior to getting symptoms. With a vaccine, the immune response is rapid so symptoms come in as soon as the virus enters your body and before you are infectious. It is severe quickly and then abates. It abates, however, just when you are becoming infectious.

[Now vaccines also likely adjust the viral load (downwards) and also the interval of time you are infectious (and the interval of time you would test positive on a rapid test). I didn’t try and play with that in this diagram because it is hard to know since, for instance, Omicron likely has a higher viral load or other properties which may limit accuracy. So I kept them the same.]

The LEFT-SHIFT in symptoms is a consequence of moving from a novel coronavirus to a non-novel coronavirus. For most of us, that shift has occurred. It means that our normal intuition that symptoms mean we are sick and dangerous holds. But it also means that during the period where symptoms abate and we are feeling better we are at our most dangerous and most complacent.

It is important to recognise that this is somewhat counter-intuitive given what we have been taught about symptoms. Our intuition — coming from the cold and flu — is that when we are coughing, sneezing or wiping our nose — we are spreading the virus. However, this is based on a theory of infectiousness whereby viruses are spread primarily by droplets that fall to surfaces and then are transmitted to others. For Covid, this has been thoroughly debunked and it may well be false for the flu as well. (Read this earlier post of mine). This means that symptoms are telling us more about what our own immune system is doing and not that much about whether we are infectious or not. However, a rapid test can tell us that part. So we need to use them precisely when we feel we won’t need them.

One question I was asked was “what about wastewater?” This was referring to the fact that we can see the coronavirus prevalent in a locality by testing wastewater. Those seem to show the presence of the virus quite early. Why isn’t that an indication of infectiousness? Now, I am not a doctor but here is my understanding based on the point of exit. Wastewater contains viral remnants that have exited through … well, you know … and for most people (I don’t want to judge) they don’t interact with others close to … well, you know … indeed, if you are like me you wear multiple layers of masking when interacting with others. By contrast, when the virus is present in your nose, then you breathe it out which means your exit point is closer to other people. So wastewater will be a leading indicator of infection but not necessarily tell us everything about infectiousness. (Unless you are a dog whereby all this doesn’t apply although it ought to and I can’t believe we didn’t select out of all that over the last few thousand years.)

You may be thinking “hey, economist, stay in your lane.” That is fair enough but frankly, on the airborne virus question I think there is ample evidence to support that (read this from The Lancet a year ago) and, moreover, that means guidelines and procedures have to catch up.

The Key Messages

Here are the key messages I need you to take away from all of this:

Isolation guidelines: you should definitely isolate yourself if you have symptoms — just as before. However, when your symptoms abate, it is likely you are still infectious. So you should “test to leave” or wear an N95 (or equivalent) mask for a few days after you are feeling better. Remember those masks are to protect others. So send your kid to school in a mask for a few days after they are sick and do the same if you go visit grandma.

You should wear masks after you are feeling better with a cold or flu. This ain’t just about Covid.

Because symptoms now indicate the potential onset of infectiousness, blanket requirements on people without symptoms are unlikely to be worth their cost. It is better to focus on post-symptomatic measures.

In other words, endemic Covid should have management practices similar to the flu and it is likely we need to significantly up our game there too.