If AI and workers were strong complements, what would we see?

The answer is pretty much what the initial data is showing

One job that AI has created is for people trying to predict what jobs AI will take. There has been an industry in this for the better part of a decade. The industry set itself a difficult challenge, however, as there was no data to go on because AI hadn’t had a chance to embark on its potential job destruction for most of that time.

Three years post ChatGPT, data is trickling in. It can only be suggestive: hence the title of the latest, and arguably most careful study to date, “Canaries in a Coal Mine?” by Erik Brynjolfsson, Bharat Chandar and Ruyu Chen. They sensibly look at the data and wonder what forward predictions it might be signalling. Of course, like a canary in a coal mine that can send a clear signal by dropping dead quickly if toxic gas is present, with job data, the search is for similar dire signals.

But before getting to their findings, I wanted to do what I do and consider what sort of facts we would see based on two extreme hypotheses: that AI substitutes for workers versus AI that complements workers.

Let’s start with the substitute hypothesis: in this scenario, AI appears, and businesses look at what it can do and decide that the AI can, more cheaply, do the jobs of existing workers. The results would be:

A shift inwards of the demand for labour, with a corresponding reduction in wages and workers employed.

The magnitude of that reduction will be large, the more relatively productive per dollar AI is compared to workers (the wage part) and the more elastic the supply of workers (the employment part). (If worker supply is inelastic, wages would have a large reduction, and employment would not.)

Moreover, as AI is substituting for human cognition, businesses would look to replace the most expensive humans first; those who had a skill and/or experience premium that was no longer valuable. Thus, reductions may be across the board but felt more with, one would imagine, older workers. This effect would be more pronounced if AI specifically substituted for skills or experience more than other stuff; something that Ajay Agrawal, Avi Goldfarb and I speculated about in our paper, “The Turing Transformation.”

Now consider the alternative complements hypothesis: in this scenario, AI appears and businesses look at what it can do and decide that AI can enhance the productivity of their existing workforce. The results would be:

A shift outwards of the demand for labour, with a corresponding increase in wages and workers employed.

The magnitude of that increase will be large, the more relatively productive workers are with AI relative to being without (the wage part) and the more elastic the supply of workers (the employment part). (If worker supply is inelastic, wages would have a large increase, and employment would not.)

Moreover, as AI is a complement to human factors, businesses would look to recruit more of the most expensive humans first; those who had a skill and/or experience premium that was now more valuable. Thus, increases may be across the board but felt more with, one would imagine, older workers. This effect would be more pronounced if AI specifically complemented skills or experience more than other stuff; something that Ajay Agrawal, Avi Goldfarb and I speculated about in our book Prediction Machines, which made the case that AI would be a complement to human judgment.

The point being is that it is possible to get some information regarding whether AI is fundamentally substituting for existing workers or complementing them from short-run data.

Having done that, let’s turn to what the paper found. It boldly stated six facts:

Early-career employment declines in AI-exposed occupations

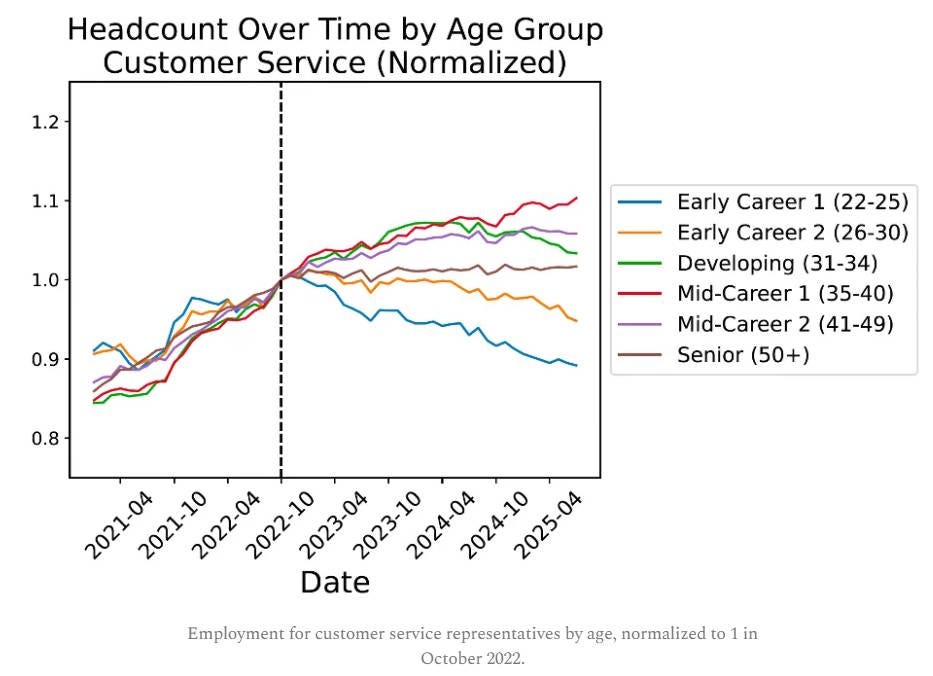

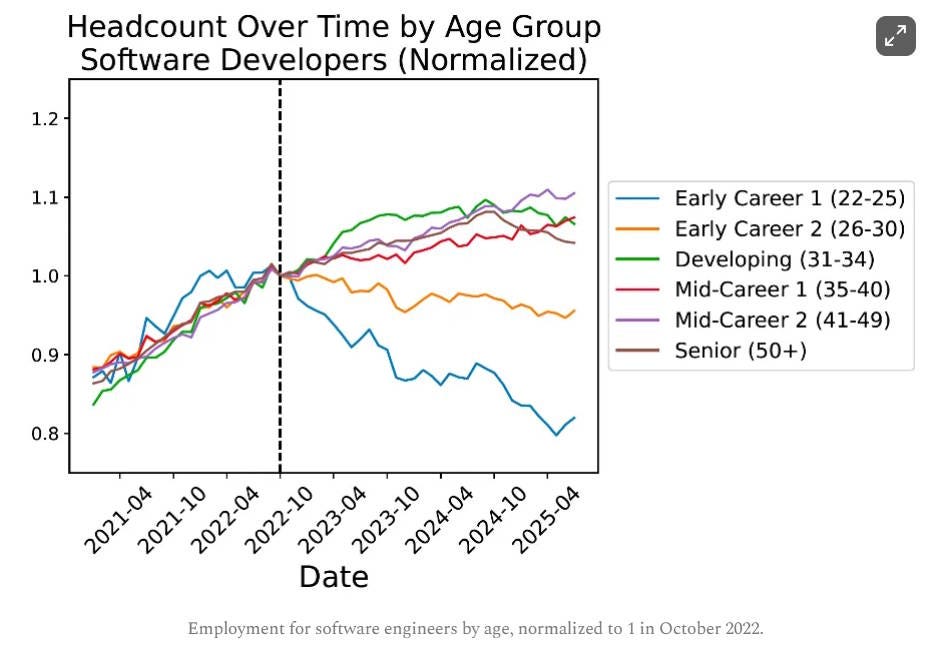

Workers aged 22–25 in fields like software development and customer service saw sharp drops in employment since late 2022, while older workers and less AI-exposed jobs remained stable or grew.Overall employment grows, but young workers stagnate

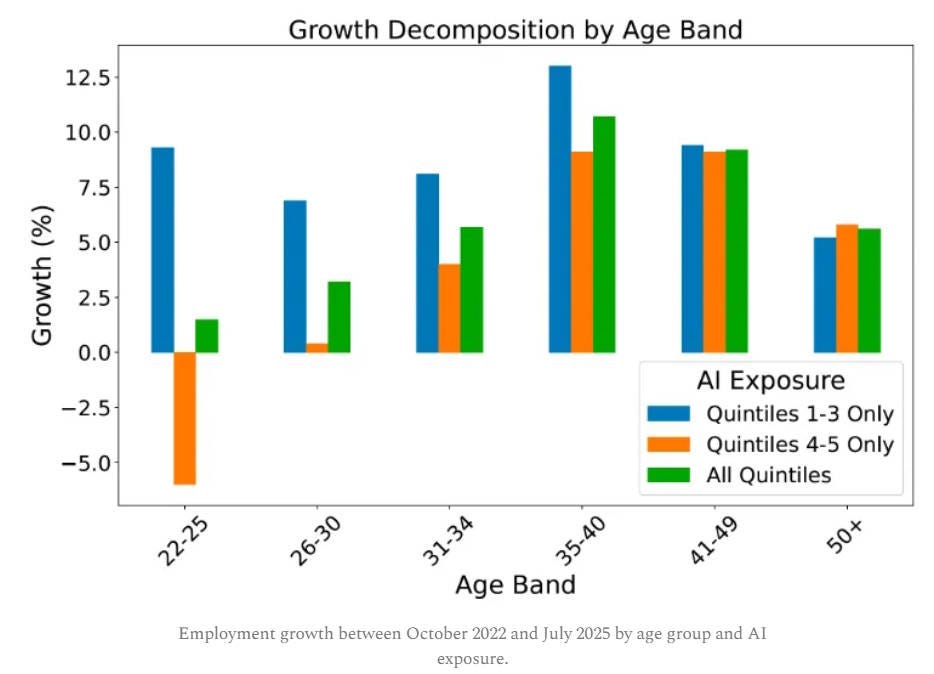

Employment in the U.S. overall has continued to rise, but growth for 22–25 year-olds stalled. In highly AI-exposed jobs, they experienced a 6% decline between late 2022 and July 2025, while older workers in the same jobs grew by 6–9%.Automation-linked AI drives declines, augmentation does not

Young workers in jobs where AI use is mainly automative (substituting for labour) faced declines, but those in jobs where AI is augmentative (complementing human work) did not. In some augmentative cases, entry-level employment even increased. (I have my own doubts about whether the automation/augmentation classification actually mirrors complements and substitutes, but that is a discussion for another day).Effects persist after controlling for firm-level shocks

Even after adjusting for firm-time shocks in a regression model, 22–25 year-olds in the most exposed quintiles still showed a 12–13% relative employment decline. This indicates results are not driven by broad industry or firm-specific shocks.Adjustments appear in employment, not compensation

Wages remained largely flat across exposure groups and ages, suggesting wage stickiness. The immediate labour market adjustment has been through employment reductions rather than pay cuts.Findings are robust across alternative checks

Patterns hold after excluding tech occupations, remote-work jobs, and during robustness tests with longer samples. They did not appear before widespread AI adoption (post-2022), nor are they explained by COVID-19 education effects. The trends are most pronounced for entry-level workers, including non-college groups up to age 40.

The paper’s takeaway that the authors tentatively endorsed (and the media widely went with) was that “generative AI has begun to significantly affect entry-level employment.” As that impact was to reduce it, the broad interpretation of this study was that it was “bad news” for jobs.

But is it? Noah Smith pointed out that the first two facts contained an alternative interpretation. As can be seen from this graph, only the youngest workers saw reductions in AI-exposed jobs. For almost everyone else, it was positive. That is, employment for older workers in AI-exposed jobs grew.

Here’s Smith:

How can we square this fact with a story about AI destroying jobs? Sure, maybe companies are reluctant to fire their long-standing workers, so that when AI causes them to need less labor, they respond by hiring less instead of by conducting mass firings. But that can’t possibly explain why companies would be rushing to hire new 40-year-old workers in those AI-exposed occupations!

Think about it. Suppose you’re a manager at a software company, and you realize that the coming of AI coding tools means that you don’t need as many software engineers. Yes, you would probably decide to hire fewer 22-year-old engineers. But would you run out and hire a ton of new 40-year-old engineers? Probably not, no! And yet Brynjolfsson et al.’s data says that this is exactly what’s been happening since 2022. Empirically speaking, it’s a great time to be a middle-aged software engineer or customer service rep!

This happened in customer service where you would think experience does count.

But also computer coding

What’s going on here? You might be tempted to say that neither the substitutes nor the complements hypotheses are bearing out. But, in fact, that is not the case. These patterns are most consistent with the complements hypothesis and not consistent with the substitutes hypothesis at all. This is because what AI complements are not being associated with a human body, but associated with a human body that has human skills. If a new technology comes along that augments the productivity of existing workers, then any business will want to hire workers with the necessary skills and experience and fewer workers who don’t have those skills. Complements do not lift all boats. It lifts the boats with the right stuff therein.

Brynjolfsson, Chandar and Chen do recognise this. They claim that younger people have more codified knowledge that they get from education, while older people have more tacit knowledge that is not so freely available. The former are available to the AIs, while the latter are not. This is potentially true, but the actual implication goes beyond this. It says that AI is complementary to those who have tacit knowledge. It increases the value of that knowledge and does not simply sit alongside it as another option for business. It is only in that respect that businesses could find it worthwhile to actually hire more older workers and fewer younger ones. The interaction matters.

If this supports the complements hypothesis, what does all of this mean? First of all, it is horribly bad news for the products of our education system. In order to be productive with AI, they need to obtain skills and experience that appear to come from learning by doing, except that they may not have the opportunities to ‘do.’ Second, wage dispersion is going to increase further; something Ajay Agrawal, Avi Goldfarb, and I hypothesised in our recent paper “The Economics of Bicycles for the Mind.” (And yes, I am aware that somehow we have managed to be right all along. It helps to explore the implications of a myriad of assumptions rather than pick and choose the ones that generate the story one wants.)

Beyond the canary, however, what does this mean for the long run? The problem it highlights is that businesses are going to run out of workers with experience. Unlike AI, they are biological, like canaries. You might wonder whether businesses should, therefore, not stop hiring younger workers in order to build up that experience. However, there are two potential strikes against that. First, when AI is present, the experience may not be the same, which could be an issue. Second, and more straightforwardly, if I hire a young worker and give them experience, that is a gift to the market and not simply my business. The costs are private and the gains are socialised, and when that happens, things tend not to happen.

It used to be considered that with respect to AI, substitutes = bad and complements = good. This paper highlights that, sadly, things aren’t that black or white.