Welcome to Plugging the Gap (my email newsletter about Covid-19 and its economics). In case you don’t know me, I’m an economist and professor at the University of Toronto. I have written lots of books including, most recently, on Covid-19. You can follow me on Twitter (@joshgans) or subscribe to this email newsletter here. (I am also part of the CDL Rapid Screening Consortium. The views expressed here are my own and should not be taken as representing organisations I work for.)

One indication that the pandemic is moving towards the end is that I have run out of things to say about it. Hence, the rare newsletters this past month. However, this week I finally went to the optometrist for my annual checkup that hadn’t happened for a couple of years and despite the likelihood that everyone there was fully vaccinated, hygiene theatre was in full swing. You touch lots of stuff there and each time that happened, it was dutifully wiped down. And masks were on despite the fact that they made eye examinations more difficult. All this indicates that we don’t know what we are doing.

The issue is a simple one: have we vaccinated enough that whatever embers of the pandemic are still with us won’t blow up into a roaring fire? In Ontario, things are looking good. Almost 80 percent of the 12+ population have received a dose and over half a second dose with the rest likely done over the next few weeks. That means that one of the longest lockdowns has effectively ended and will end by next Friday. But no one is willing to abandon the theatre yet. Indeed, there are indications that even if we do so, we might end with a new show, which I call, vaccine theatre, in which people require vaccines to come to places where everyone is likely to be vaccinated and, if not, it is their own choice rather than a medical issue. But more on that in a future newsletter.

For now, I want to know, what is it going to take to convince us that things are OK?

The world is running a series of experiments to determine this. For example:

The UK: no restrictions despite the Delta variant growing at pandemic rates.

The US: no restrictions but with significant inter-state and inter-county variation in vaccine rates.

Ontario: high vaccination with limited restrictions (including indoor mask-wearing)

NSW: a lockdown with low vaccination rates and Delta running ahead of previously successful contact tracing.

Japan: holding a single event with 20,000 international visitors.

There are likely others. Are any of these experiments good in the sense that they will give us the information we need to manage the pandemic going forward?

The NSW and Japanese experiments are the most uninformative. That is because they are not really experiments at all. Instead, they will tell us how the usual management tools are working when there is Delta but significant but low vaccination rates. I personally think Japan had an opportunity to do much better while NSW and Australia, in general, is grappling with denial that the ‘obvious to everyone else’ fact is that the eradication strategy will be no longer feasible once everyone who wants to be vaccinated is vaccinated.

The Ontario experiment also isn’t really an experiment. To be sure, if, under these conditions, Delta spreads and we see an increase in health problems and fatalities, we are all going to realise that there is no endgame and perhaps Covid-19 management will be a fact of life. In that case, it is more grist to the mill for rapid screening and will hopefully convince people that hygiene theatre isn’t doing its intended non-theatrical job.

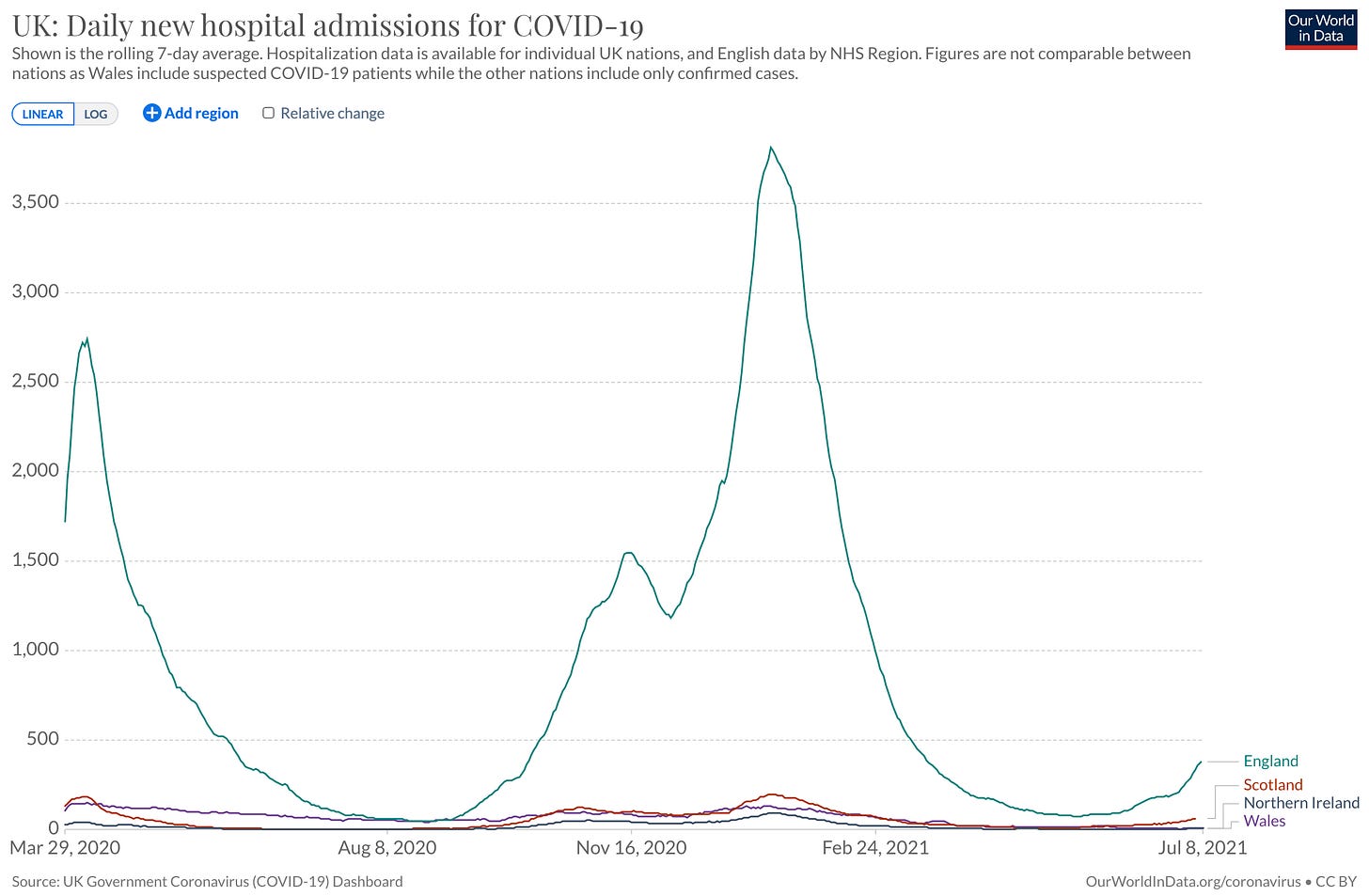

The UK is an experiment that has a chance of leading to a very clear signal of something: if you open up in the face of Delta and you avoid health costs that is very good news. But it is far from certain. Will the virus spread and what will the health outcomes be? On viral spread, we have our answer I think:

That’s not good for a country with one of the highest vaccination rates in the world. That said, the vaccine was not available for the under 25’s until recently which makes the whole thing weird. But this graph is the really worrying one.

So while the UK experiment had the potential to yield a clear signal, it is really playing with lives here. No one really thought the UK was ready for it. Yes, it will be useful to us to know the experimental outcome but the cost seems potentially extreme.

That leaves the US. It is a pretty good experiment. For starters, most of those who want the vaccine have obtained it. There are issues — access, misinformation and so on — but those are not problems that are easily solved. But there is significant cross-regional variation.

But what will that experiment tell us? Like the UK, in states where there is relatively low vaccination, it will likely tell us little as we are already seeing cases and hospitalisations rise. What it does tell us is whether, with open borders, outbreaks in one state spread to other states with higher vaccination levels. This is the kind of thing that many countries want to know in terms of opening their own borders. And it is something that (a) we really don’t know the answer to and (b) that, for states/counties, with high vaccination rates, it is an experiment with relatively lower costs.

What that means is that all eyes are back on the US. What the US is doing will tell us more about the endgame for the pandemic at a global level. But it may take until the end of 2021 before the results are in and the picture is clearer.