Compute, compute, compute!

What are the consequences of the massive proposed AI investments

There is a massive amount of investment going into AI at the moment. Leaving aside applications, there is a race to build foundational models. This week, Anthropic released Claude 3.0, which means that we now have three GPT-4 level foundational models in the wild (well, almost in the wild; Claude 3.0 is not available in Canada). But no one seems to be denying that there is a new race for a GPT-5 level model, whatever that means. Basically, everyone has decided that some sort of scaling law applies to AI and that you can extend measured technical performance (emphasis foreboding) by leaps and bounds by 10x’ing investments.

I have to say that exact numbers on the costs of training these models do not seem to be available in any concrete sense. Lots of people seem to claim that GPT 3.5 cost around $100m, GPT 4 cost around $1 billion and the next version around $5 billion or more. But there are claims that some version of these models might be trained for $100 billion or more in the very near future, which is, from an economics standpoint, a mind-boggling amount. Then there are claims that Sam Altman is trying to raise $7 trillion, which is a whole other level.

All of this both emphasises the importance of compute — the chips and power to train AI models — and whether the entire exercise is likely to be an economic one. I am very bullish on AI and want more sooner, but the hard-headed economist in me can’t help but wonder if such acceleration is justified. I am not talking about all of the debate about the potential harms from AI here, I am just talking about the plain old rate of return.

Given this, perhaps it is time to remind ourselves of some of the basic principles of investment just to ensure there is some grounding to all of this talk.

Principle 1: Invest when costs are low

Around the time of the global financial crisis, I suggested to the Australian government that it would be a great time to undertake a big public infrastructure investment in fibre to the home broadband. At the time, broadband in Australia was terrible, and investment was in the hands of a monopolist. But my big point was capital was cheap and other countries wouldn’t be making big investments so stuff like fibre might be cheap as well. It would be a good time to build.

Now consider today for foundational AI models: is it a good time to build? It sure does not look like it. Capital is expensive, with high interest rates worldwide. But more critically, chips are expensive — that NVIDIA valuation didn’t come from abundance. That suggests that waiting to make such big investments ought to be the default rather than acceleration.

Principle 2: Invest when demand is known

Now, you are probably thinking, “Hang on a minute! Where is he going with this? Isn’t the one thing we do know is that there is a ton of demand for AI?”

Well, sure. There seems to be a lot of demand for AI applications. But what I am less certain about are marginal applications. Do we know, for instance, that spending ten times as much on GPT 4 will lead to 10 times the value of using GPT 3.5? Remember that the first use was effectively a zero to one margin of value. The move from 3.5 to 4 would be, at least in the short-run, surely less than that. It isn’t called the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility for nothing.

I mean that quite seriously. Yes, we lead users often use GPT 4 because it is there. But when push comes to shove, how many of the use cases for GPT 4 could not easily be done with GPT 3.5? We developed an AllDay-TA for our classes here at Rotman and have found GPT 3.5 to be more than enough for the task and so we have hesitated to do a GPT 4 version simply because of the increasing in potential running costs.

If we don’t really know what the marginal value of the previous version of the investment was, how could we forecast the marginal version of the next, especially since a scaling law governs it? Users just haven’t had enough time with the current version in order to work out what its real value is and what exactly is missing. Seen in this light, the investment activity in training is all about, “We will work that out later. Right now we are in a race.” My point is that being in a race is fine, but it is better when you know what the prize is.

Principle 3: Invest when there is high “scrap value”

Uncertainty surrounds lots of investments. One way to deal with that if you don’t have enough information upfront is to invest in things you can repurpose. Chips can be repurposed, power cannot. So, there is a red flag right there in training foundational AI models.

But chips are a durable good. That’s good news in that training chips may be used for “inference” (that is, running the AI models thereafter). But I don’t know if those two uses match up. Nor do we know if the marginal costs of that will be too high or if people will want to run these models in the cloud. (For instance, Apple are betting on specialised Neural Engine chips on every device to handle that.). What is likely, therefore, is the chips are going to be manufactured and deployed in training, and then there will be a glut of them. All this adds up to considerable doubts about their scrap value.

Summary

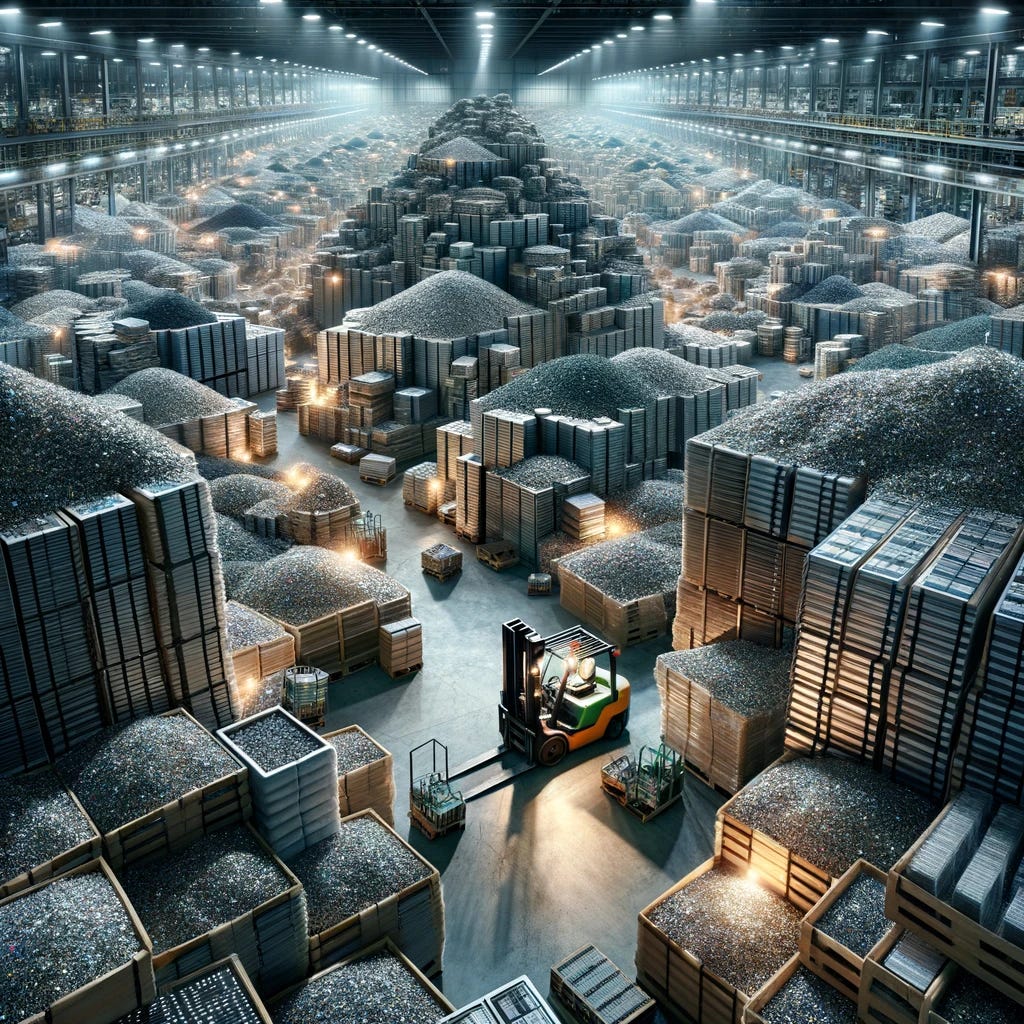

People are very enthusiastic about compute. They want more of it. I have even heard talk of making it a publicly owned good so everyone can have some compute and so have power in some post-scarcity economic paradise.

But this is the time for me to wear my economist’s dismal badge on my sleeve and point out that some of the big numbers people are throwing about do not appear to have a good business case for them. To be sure, I am saying the case isn’t there to do this right now. That is not to deny that it wouldn’t make sense as part of a slower pace of investment for the future.

Oh yeah, that Australian broadband proposal. The Australian government actually did what I suggested but they ended up doing it slowly and in cahoots with the monopolist I was trying to avoid and it ended up costing a ton more as a result without delivering the promised value to consumers. I wanted quick action. They wanted a quick announcement.

My point remains: it is time to take a breath and enjoy and build on what we currently have.