AI pioneer, Geoff Hinton, has changed his mind

Should we now start worrying about AI?

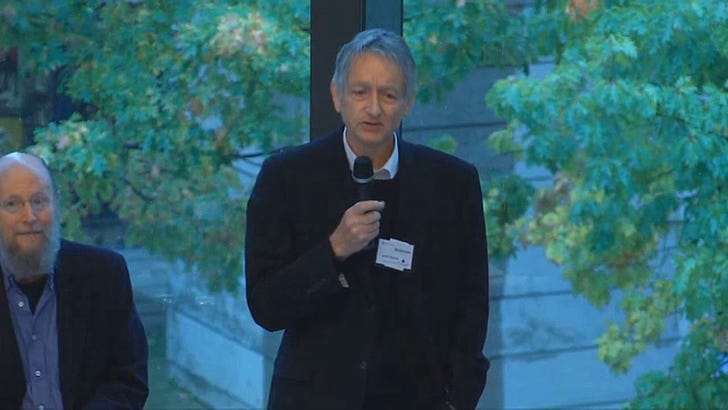

Geoff Hinton, University of Toronto professor, Turing award winner, and one the people most responsible for the invention of prediction machines (the current wave of what people refer to as AI), has changed his mind. As reported in the New York Times, Hinton is now worried about the thing he created. This Dr Frankenstein moment is a hard pivot for Hinton. For much of the past decade, he has been working with Google to improve prediction machines; Google declared a few years back that it was now an AI-first company. In 2017, here at a conference at Rotman, Hinton famous declared, “people should stop training radiologists now.” He didn’t regard that as a bad thing but “as business as usual.”

Not surprisingly, that has got people’s attention.

This all comes after a tumultuous few months since ChatGPT exploded onto the scene. There are many people in the tech field expressing worry. There was the infamous pause letter, including Elon Musk as a signatory to people like Eliezer Yudkowsky, who thinks we should just stop attempting to build machines more intelligent than people as it is too dangerous.

Many researchers steeped in these issues, including myself, expect that the most likely result of building a superhumanly smart AI, under anything remotely like the current circumstances, is that literally everyone on Earth will die. Not as in “maybe possibly some remote chance,” but as in “that is the obvious thing that would happen.” It’s not that you can’t, in principle, survive creating something much smarter than you; it’s that it would require precision and preparation and new scientific insights, and probably not having AI systems composed of giant inscrutable arrays of fractional numbers.

He goes on.

If somebody builds a too-powerful AI, under present conditions, I expect that every single member of the human species and all biological life on Earth dies shortly thereafter.

Hey, stop hedging your bets and be clearer, Cassandra! For his part, Hinton sighs, “I console myself with the normal excuse: If I hadn’t done it, somebody else would have.” Yeah, sure, but there were not many people who took a thirty-year bet on neural networks and ended up proving everyone else wrong.

Given all of this, I figured it was time to point out that all of these people are worried about very different things. And that is important because it matters for how we actually approach dealing with it.

The Short-Run Hinton Concern

Geoff Hinton didn’t invent the Short-run Hinton concern, but it is convenient to associate it with him right now. That concern is this:

His immediate concern is that the internet will be flooded with false photos, videos and text, and the average person will “not be able to know what is true anymore.”

Basically, it has now become cheap to make fake stuff, so people will make a ton of fake stuff, and it will be all over the Internet. In that world, what will people do?

The subtext here is that all information available on the Internet will be subject to doubt, and so the Internet will lose its primary gift to us — the gift of information accessible worldwide.

I’ll say right now that he is likely right that we will be flooded with fake stuff. That is another part of the “mess” that is produced by new AI tools. But we need to consider the equilibrium as the notion that it is hard to know what is true when you read or otherwise consume information is a very old one and one that society has persistently had to deal with. Just read Jill Lepore’s fabulous treatise, These Truths.

What happens when information cannot be trusted is that the market supplies trusted sources. These might be people or websites or something else where you can be assured of something’s authorship or attestation. Then it is the reputation of the author or publisher that sustains trust. Indeed, a report I co-authored a few years back argued that it would be great if we could establish a framework whereby information could be easily tracked back to its source. That would be a technological substrate that would accelerate the market response to fake information.

The upshot is the messy few years of fake information that AI may cause will resolve itself in a new equilibrium. At that point, we will lament that there are so few trusted voices, but we will move on.

The Long-Run Hinton Concern

Geoff Hinton, for sure, didn’t invent the long-run Hinton Concern. That probably lies in Mary Shelley in a path through Isaac Asimov and Nick Bostrom. But Hinton has come to the party being shocked at the rapid pace of change these last few years.

Down the road, he is worried that future versions of the technology pose a threat to humanity because they often learn unexpected behavior from the vast amounts of data they analyze. This becomes an issue, he said, as individuals and companies allow A.I. systems not only to generate their own computer code but actually run that code on their own. And he fears a day when truly autonomous weapons — those killer robots — become reality.

“The idea that this stuff could actually get smarter than people — a few people believed that,” he said. “But most people thought it was way off. And I thought it was way off. I thought it was 30 to 50 years or even longer away. Obviously, I no longer think that.”

So he’s gone from “sorry not sorry about radiologists” to “it may come for all of us.” And he has seen the Google stuff we haven’t seen.

The jobs issue is a tricky one and one that requires a longer post to deal with. Hinton is worried that AI may represent an existential threat to people.

There are many people who believe that superintelligent AI is possible (I would count myself as one of them), and there are people who believe it is coming quite fast (I’m not so sure of that). But there are some steps from creating a superintelligent AI to wiping out all of humanity.

Here’s the short version of Yudkowsky:

Without that precision and preparation, the most likely outcome is AI that does not do what we want, and does not care for us nor for sentient life in general. That kind of caring is something that could in principle be imbued into an AI but we are not ready and do not currently know how.

Absent that caring, we get “the AI does not love you, nor does it hate you, and you are made of atoms it can use for something else.”

Actually, it kind of resonates with me as an economist. The AI may want resources just as we do, and so will eliminate the competition. At the same time, however, we are also a resource. Is it obvious that the AI will want to get rid of a resource?

The question then becomes: why are we such a problem for AI? I mean, the assumption is that if a thing emerges that is super smart, it is more likely than not that it will think the smart thing to do is to get rid of us. What does that say about us? It’s not a good look morally or economically.

That said, if you really think that AI is going to kill us all, then raising the alarm is the least you should do. So I get that. If using a chatbot to save time crafting a memo is a road to killing your grandchildren and everyone else, that at least poses a dilemma.

An Economic Approach

Again one newsletter can’t parse these issues. But interestingly, a new paper by economist Chad Jones starts to frame all of these existential worries in an arguably more sensible light. Jones starts with two assumptions that I would term “the full Yudkowsky":

There is a non-zero probability that superintelligent AI will kill us all

We can actually stop AI development

Now, in the debate thus far, there have been arguments about these assumptions, but most seem to accept that if these assumptions hold, then we should stop AI development. But Jones, accepting these assumptions as a starting point, shows that reasoning is flawed.

The reasoning is that, up until the moment Skynet kills us all, AI generates productivity improvements that we enjoy. So even if pausing AI development is possible, there is still the question of whether we would want to. This is because there is a period of time when we could enjoy AI, and if we knew the point where it was going to get out of hand, just stop it then. Of course, it is hard to know when that point is near because things might move too fast for us to hit the stop button. Thus, at every point in time, we have to trade off the utility benefits we get from AI against the risk that during that period, we might miss the opportunity to stop the AI from crossing the existential line.

Jones shows that what really matters is how much we enjoy the riches AI might bring before it kills us all. If the riches are v per person alive today, then so long as this is less than the growth in riches divided by the probability that AI wipes us out in the next period — a measure of the benefits (growth) to costs (risk) of AI — the idea being that we lose v for everyone who dies.

In some situations, because all of this is involving things accelerating at a fast pace, you can get situations where if the annual risk of evil AI occurring is 1 percent you would comfortably continue development for many decades, but if it was 2 percent you would shut it down now. Put another way; you would actually take a 50-fold increase in what you can consume for anything less of a 1 in 3 chance of AI killing us all over the same period of time. For a model starting at a pessimistic place, that is quite a lot of breathing space.

If we run out of our joy for new things, the picture changes. You want to run the AI until we get as happy as we are going to get and then stop. If AI accelerated growth to 10 percent a year, we would be done with AI in 4 to 5 years. We mine it for what we need and then turn it off. That said, Jones points out that if we think about poorer people in the world, they are going to want to run the AI for longer. This suggests a wealth divide in terms of who is going to be concerned about AI risk.

An exception to all of this comes from the possibility that AI may improve our mortality rates. Jones then shows that we are more than happy to live with lots of AI risk because the AI is giving that extra life, which means you are no longer trading off the utility from our short lives with a once-off existential event. Longer life puts the trade-off on the same terms.

The point here is not that this type of analysis gives us comfort regarding AI risk but that it allows us to consider both the benefits and costs of AI rather than just focusing on the latter.

My broader point is that I am not sure we should leave the philosophy and AI policy to the AI innovators. If we are going to have a debate about these issues, we need to accept that there are no obvious answers and to work out carefully what risks we find acceptable to bear, given the upside of all of this.