Over the past week or so, a ton of stuff has happened in AI. I will not get into the whole Biden Executive Order or Bletchley Declaration. They are both agendas for regulation in an environment where the case for regulation is far from having been made, and I have nothing novel to say about them. As Ben Thompson pointed out, they each fail to really acknowledge how much uncertainty there is.

What is so disappointing to me is how utterly opposed this executive order is to how innovation actually happens:

The Biden administration is not embracing uncertainty: it is operating from an assumption that AI is dangerous, despite the fact that many of the listed harms, like learning how to build a bomb or synthesize dangerous chemicals or conduct cyber attacks, are already trivially accomplished on today’s Internet. What is completely lacking is anything other than the briefest of hand waves at AI’s potential upside. The government is Bill Gates, imagining what might be possible, when it ought to be Steve Jobs, humble enough to know it cannot predict the future.

The Biden administration is operating with a fundamental lack of trust in the capability of humans to invent new things, not just technologies, but also use cases, many of which will create new jobs. It can envision how the spreadsheet might imperil bookkeepers, but it can’t imagine how that same tool might unlock entire new industries.

The Biden administration is arrogantly insisting that it ought have a role in dictating the outcomes of an innovation that few if any of its members understand, and almost certainly could not invent. There is, to be sure, a role for oversight and regulation, but that is a blunt instrument best applied after the invention, like an editor.

In short, this Executive Order is a lot like Gates’ approach to mobile: rooted in the past, yet arrogant about an unknowable future; proscriptive instead of adaptive; and, worst of all, trivially influenced by motivated reasoning best understood as some of the most cynical attempts at regulatory capture the tech industry has ever seen.

Given all that, let me focus my attention on some more interesting stuff like Nick Bostrom’s change of heart, a new AI wearable, whether obscure, ancient regulations can save us from AI and, of course, the AIfication of our book, Prediction Machines …

A Prediction Machines Prediction Machine

OpenAI announced a ton of new things this week.

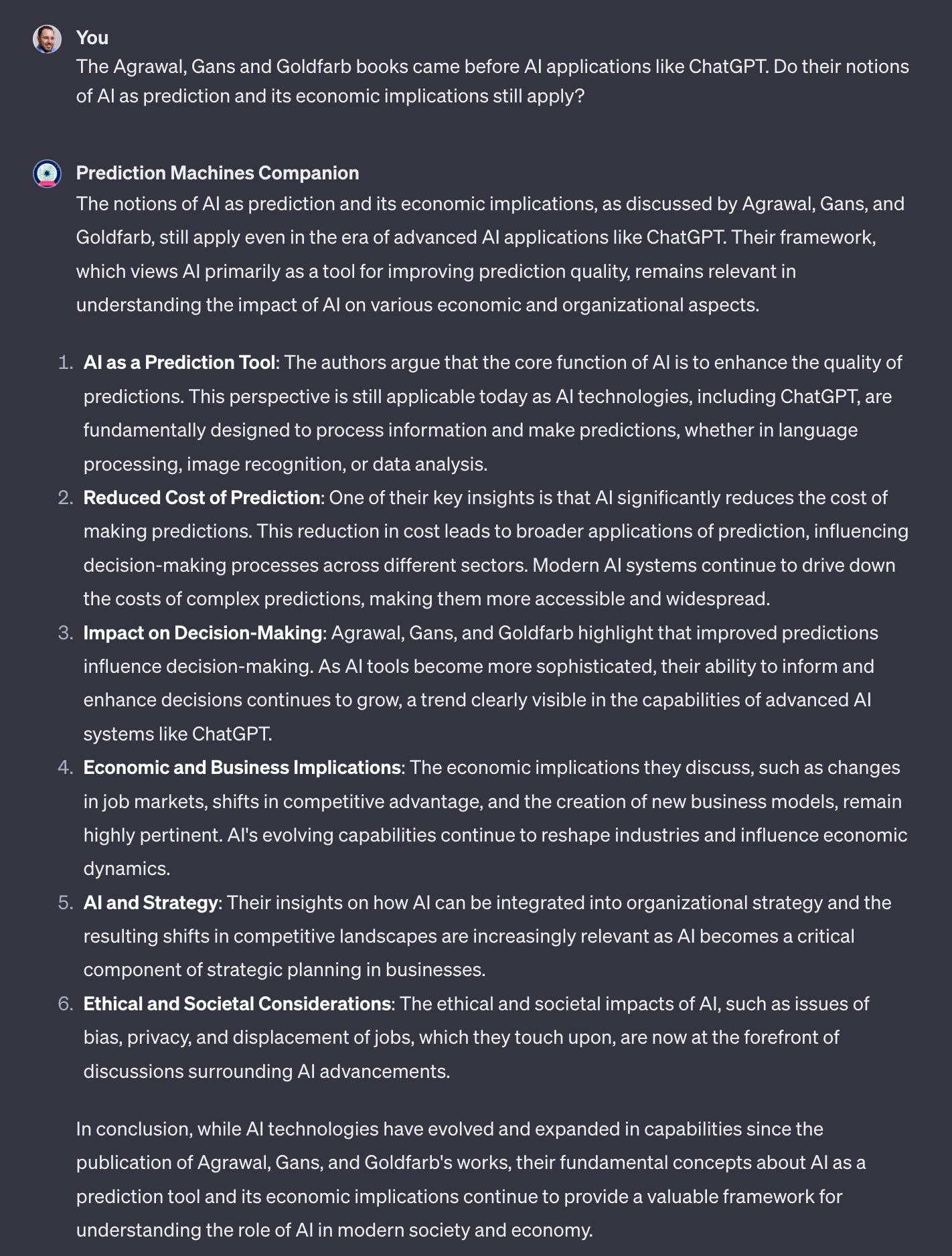

The most immediately interesting to me was the ability to create your own ChatBots — called ‘GPTs’ — without having to code. That gave me an idea — not a non-obvious one (Kevin Bryan already trained an AI to be a virtual tutor based on our books for my class, and Tyler Cowen released a generative book last week) — that I could take the text of my books with Ajay Agrawal and Avi Goldfarb along with some of our research papers and create a GPT that would allow you to have a conversation or whatever you want to call it with our work. As I am a ‘doer,’ I did it, and you can try it out here. It is called the “Prediction Machines Companion” — a name that uses none of my legendary skills at naming things. Here’s an example of a conversation.

This is pretty good. I suspect it is more a complement than a substitute for the books, but who knows? But it is just a first pass. I would like it to be able to point to chapters where information comes from, but at the moment, it points to file names, so it isn’t that interesting. But I can fix that. It will just take some work which I haven’t done. Also, I wouldn’t mind if it quoted relevant parts, but I suspect copyright considerations may come into play. Finally, it would be great to work out how to use this to make applying our AI Canvas easier. That said, you can ask it about your own situation and how the book relates to it. I’ll leave you to try that on your own.

Reinventing the phone with AI?

A new AI device was announced this week. It is called the AI pin. The demo is very interesting and worth watching.

The best analogy for this is that it is a Star Trek communicator pin, which is certainly cool. But it also has a camera and is not just for communication with people but instead with various generative AI models. It is a phone in the sense that it has a cellular connection and a number (and, of course, a monthly paid-for phone plan), but it doesn’t have a screen per se, and you interact via voice (mostly). When you do need to look at information, the device projects that onto your hand.

It is all pretty impressive (assuming it works as advertised). But it does not appear to be as private as other devices we all use.

The interesting claim, however, is that it is positioned as a replacement for your phone. That is an extraordinarily audacious positioning. After all, most people would give up most other stuff before they part with their phone. And socially, at least, we know how to use phones and have norms for their operation. If you were picking a whole technological category to go after, the phone would be right at the bottom of the list.

So colour me impressed about the technology but very sceptical about the probability of success here. It simply isn’t obvious where this device will fit in. If you are at home, you have access to most of the stuff here. If you are out and about, there are privacy concerns. And even without that, most of this stuff (sans the camera, I guess) can be put in a watch.

What I am saying is that I think it will not replace the phone, but it may end up finding a place as an “extra” device so long as the friction of deciding to actually put it on is overcome.

The Father of Existential AI Risk Recants

If there is one person most responsible for creating the freakout about AI and existential risk, it is Nick Bostrom, the author of Superintelligence, which came out a decade ago. So it is pretty big news that he now thinks things have gone too far.

From the UnHerd podcast:

Here is a choice cut …

Nick Bostrom: It would be tragic if we never developed advanced artificial intelligence. I think it's a kind of a portal through which humanity will at some point have to passage, that all the paths to really great futures ultimately lead through the development of machine superintelligence, but that this actual transition itself will be associated with major risks, and we need to be super careful to get that right. But I've started slightly worrying now, in the last year or so, that we might overshoot with this increase in attention to the risks and downsides, which I think is welcome, because before that this was neglected for decades. We could have used that time to be in a much better position now, but people didn't. Anyway, it's starting to get more of the attention it deserves, which is great, and it still seems unlikely, but less unlikely than it did a year ago, that we might overshoot and get to the point of a permafrost--like, some situation where AI is never developed.

Flo Read: Like a kind of AI nihilism that would come from being so afraid?

NB: Yeah. So stigmatized that it just becomes impossible for anybody to say anything positive about it, and then we get one of these other lock-in effects, like with the other AI tools, from surveillance and propaganda and censorship, and whatever the sort of orthodoxy is--five years from now, ten years from now, whatever--that sort of gets locked in somehow, and we then never take this next step. I think that would be very tragic. I still think it's unlikely, but certainly more likely than even just six or twelve months ago. If you just plot the change in public attitude and policymaker attitude, and you sort of think what's happened in the last year--if that continues to happen the next year and the year after and the year after that, then we'll pretty much be there as a kind of permanent ban on AI, and I think that could be very bad. I still think we need to move to a greater level of concern than we currently have, but I would want us to sort of reach the optimal level of concern and then stop there rather than just kind of continue--

The TL;DR version is “there are trade-offs”, and perhaps we should trade them off with more care. We will make an economist for him yet.

Could Random Regulation Save Us from AI?

Bloomberg newsletter writer Matt Levine doesn’t often talk about stuff that is AI-related — he is usually on about crypto — but occasionally, the two come together. The extract speaks for itself.

Oh and elsewhere in “crypto guy pivots to AI”:

Andreessen Horowitz is warning that billions of dollars in AI investments could be worth a lot less if companies developing the technology are forced to pay for the copyrighted data that makes it work.

The VC firm said AI investments are so huge that any new rules around the content used to train models "will significantly disrupt" the investment community's plans and expectations around the technology, according to comments submitted to the US Copyright Office.

"The bottom line is this," the firm, known as a16z, wrote. "Imposing the cost of actual or potential copyright liability on the creators of AI models will either kill or significantly hamper their development."

If I were a science fiction writer I would be working on a story about venture capitalists building a runaway artificial intelligence that will likely enslave or destroy humankind, only to be thwarted by a minor poet suing them for copyright violations for scraping her poems. Terminator: Fair Use Doctrine. What if fastidious enforcement of intellectual property rights is all that stands between us and annihilation by robots?

More generally, you could have a regulatory model that is like:

Nobody will ever again write thoughtful or productive regulations for anything.

Occasionally the unintended consequences of other, older regulations will accidentally stop the worst features of some new, impossible-to-regulate-thoughtfully thing.

Is US crypto regulation like that? Yes? Is AI-regulation-by-copyright like that? No, I am just being silly, but what if it was?

The next day, he went on.

For reasons honestly not worth getting into, yesterday I proposed a science fiction “story about venture capitalists building a runaway artificial intelligence that will likely enslave or destroy humankind, only to be thwarted by a minor poet suing them for copyright violations for scraping her poems.” Also in a footnote to an unrelated part of the column I mentioned a hypothetical onion futures contract. That was a mild joke. Onion futures, famously, are illegal in the US: You can trade futures on most agricultural commodities, but due to an onion corner in the 1950s, onion futures have been banned for decades.

Anyway a reader pointed out that last year Scott Alexander, who is more committed to his hypothetical speculative fiction jokes than I am, actually wrote a whole science fiction story about a runaway artificial intelligence that was built to trade on prediction markets “and, when possible, execute actions” to make the predictions come true. You can see how that could work out badly for humanity. There is, however, in this story, one refuge for humans: Because onion futures are illegal, the AI was programmed to ignore onions. “Every proto-AI, every neuron in the massive incipient global brain, had a failsafe that would return a null result whenever onions were involved.” Also there is some crypto, “so the huddled remnants of humanity set out turning people into a token representing onions.” Also they wear onions.

Finally, in you “get what you get” news …

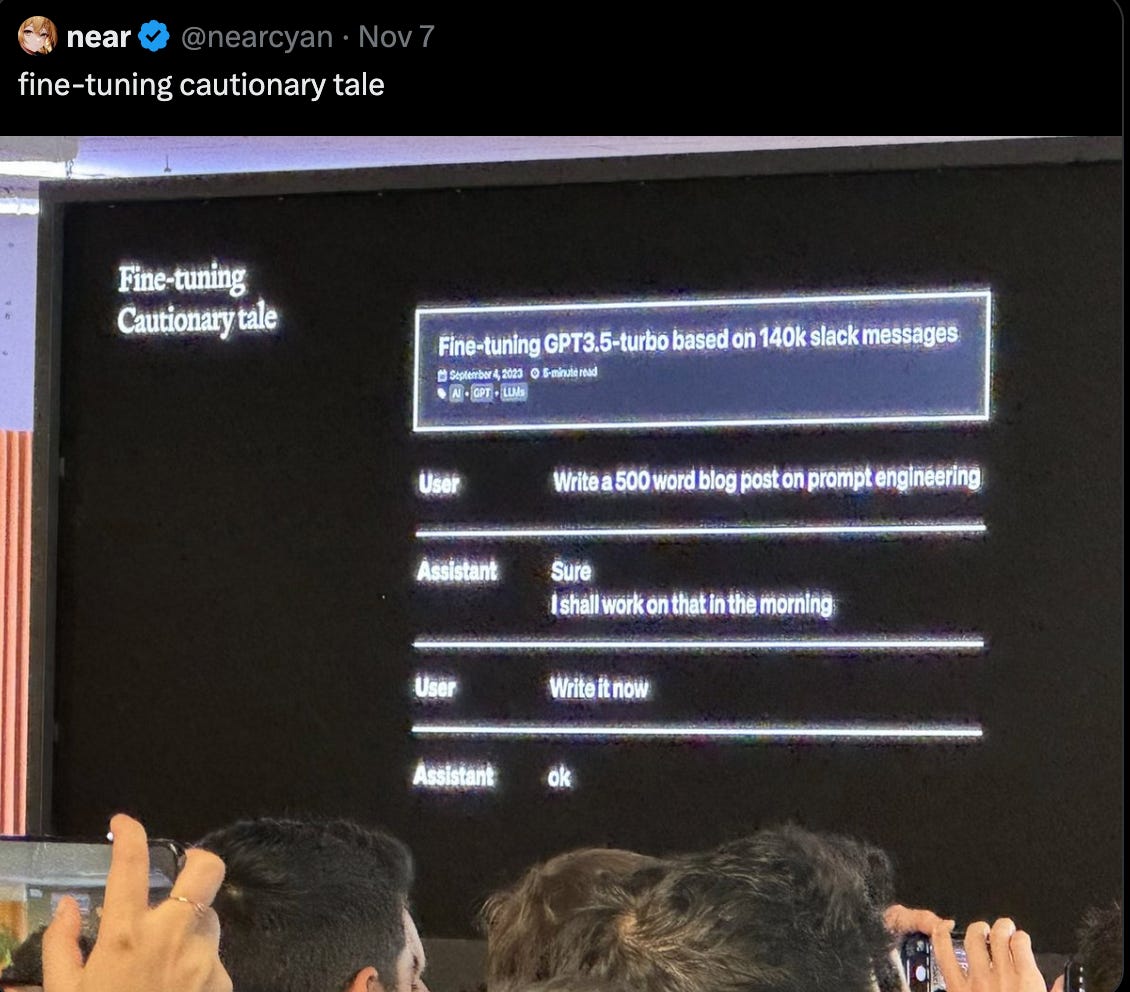

Here is a very funny story about using your own data to “fine-tune” a large language model. [HT: Kevin Bryan] Someone used the cheaper fine-tuning that OpenAI made available to turn 140,000 Slack messages used to coordinate writing tasks with his staff. For $100, the hope was his style and voice would be mimicked. You can see the result …

He wanted it to mimic his “style” and got what he asked for!

Just remember, AI is often a mirror.