Welcome to Plugging the Gap (my email newsletter about Covid-19 and its economics). In case you don’t know me, I’m an economist and professor at the University of Toronto. I have written lots of books including, most recently, on Covid-19. You can follow me on Twitter (@joshgans) or subscribe to this email newsletter here. (I am also part of the CDL Rapid Screening Consortium. The views expressed here are my own and should not be taken as representing organisations I work for.)

One of the fun ways of learning science at school was the “can you believe that people used to believe” trope. It goes like this, “can you believe that people used to believe there were just four elements?”, “can you believe that people used to believe that the sun went around the Earth?” or “can you believe that people used to believe that babies were delivered by storks?” and then you are enlightened that “there are ton of elements,” “the Earth goes around the sun,” and “you should ask your parents that one.” Well, there is a new one now: “can you believe that people used to believe that any particle that was more that 5 microns would fall to the ground rather than stay in the air?”

Some context. By now you know that up until very recently, public health authorities were telling everyone that Covid-19 was spread via droplets rather than aerosols. This is one of those things we didn’t have to know about before but the distinction really matters. When a virus spreads via droplets, you have to worry about surfaces and how people touching them spread the virus to one another. The mitigation is to clean surfaces, wash your hands, shake other people’s hands and not touch your face. This is why, at the beginning of the pandemic, that is what people were told to do. That also led to this classic of a press conference.

It also led to the six feet rule (or hockey stick rule as is the standard unit of measurement in Canada) with the idea being that if someone coughed on you, the droplets could leave them and land right in your mouth, nose or hands.

By contrast, if a virus is spread in the air, people breathe it out, it remains there for a time and so when other people come in, they breathe the same air. You know this effect via experience such as being a parent of a teenager and thinking “how does it still smell like this after she has been out of this room all day?” The measles, with its high infectivity, spread this way. It is for this reason that wearing masks is a good idea and why you worry more about indoor spread than outdoor spread which is related to ventilation.

The other week the WHO followed by the CDC changed the information with regard to how Covid-19 spread:

Previously, it has been this:

In other words, for over a year, health authorities were advising people that Covid-19 spread by droplets but changed that to aerosol transmission which they had only mentioned as a possibility before.

That distinction really matters because it causes us to change what we do. Here is Zeynep Tufecki:

If the importance of aerosol transmission had been accepted early, we would have been told from the beginning that it was much safer outdoors, where these small particles disperse more easily, as long as you avoid close, prolonged contact with others. We would have tried to make sure indoor spaces were well ventilated, with air filtered as necessary. Instead of blanket rules on gatherings, we would have targeted conditions that can produce superspreading events: people in poorly ventilated indoor spaces, especially if engaged over time in activities that increase aerosol production, like shouting and singing. We would have started using masks more quickly, and we would have paid more attention to their fit, too. And we would have been less obsessed with cleaning surfaces.

I actually am not so sure it would have mattered as much for pandemic spread — although ventilation is something that wasn’t emphasised — because we did start wearing masks in fairly short order and have kept our distance from people. People seemed to have a model of aerosol transmission in their minds regardless of what the WHO was saying.

But it most definitely would have prevented a lot of waste and cost. Billions have been spent on various means of protecting us from droplets. And they continue to be spent. And they have their own potential health costs. After all, disinfecting all of the time doesn’t seem like something that would be good for our health. (That said, I have no idea why there was no anti-hand washing movement. You should see my skin!) And it also led to hygiene theatre of which my favourite example is this:

And all of that stuff hasn’t stopped.

But the real puzzle here is: why did it take so long for the advice to change?

One clue is here. Simple inertia:

Mary-Louise McLaws, an epidemiologist at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, and a member of the W.H.O. committees that craft infection prevention and control guidance, wanted all this examined but knew the stakes made it harder to overcome the resistance. She told The Times last year, “If we started revisiting airflow, we would have to be prepared to change a lot of what we do.” She said it was a very good idea, but she added, “It will cause an enormous shudder through the infection control society.”

There is a sense in which we can all relate to that but the stakes here were too high to give in to inertia.

What’s more amazing is that this was part of the “can you believe” trope for infectious diseases in that “can you believe that people used to believe that disease did not travel via microscopic germs?”

But clear evidence doesn’t easily overturn tradition or overcome entrenched feelings and egos. John Snow, often credited as the first scientific epidemiologist, showed that a contaminated well was responsible for a 1854 London cholera epidemic by removing the suspected pump’s handle and documenting how the cases plummeted afterward. Many other scientists and officials wouldn’t believe him for 12 years, when the link to a water source showed up again and became harder to deny. (He died years earlier.)

Similarly, when the Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis realized the importance of washing hands to protect patients, he lost his job and was widely condemned by disbelieving colleagues. He wasn’t always the most tactful communicator, and his colleagues resented his brash implication that they were harming their patients (even though they were). These doctors continued to kill their patients through cross-contamination for decades, despite clear evidence showing how death rates had plummeted in the few wards where midwives and Dr. Semmelweis had succeeded in introducing routine hand hygiene. He ultimately died of an infected wound.

Disentangling causation is difficult, too, because of confusing correlations and conflations. Terrible smells frequently overlap with unsanitary conditions that can contribute to ill health, and in mid-19th-century London, death rates from cholera were higher in parts of the city with poor living conditions.

So the experts in the field knew that their predecessors had been wrong before. You might think that would make them wary of assumptions.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the assumption was that respiratory diseases like influenza and Covid-19 involved large particles and so spread via droplets. But there was very early evidence of this not being the case — from the Diamond Princess cruise ship where people were getting Covid despite being isolated, to a church where lots of people were infected despite being more than six feet apart, to early studies from China documenting such spread quite carefully. And we all know now that it was hard to find evidence of outdoor spread. Indeed, the whole notion of asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic spread — you know, before people were coughing and sneezing — was itself a strike in favour of aerosols. So much for “following the science.” Or, more to the point, what science were they following?

5-microns

It turns out, they were following what could be termed a “stylised fact” or “rule of thumb.” The background is in this paper and this Wired article. The fact relied upon is that any particular larger than 5 microns (or 0.000001651 hockey sticks) will fall to the ground so that aerosol transmission only applies if a virus is smaller than 5 microns.

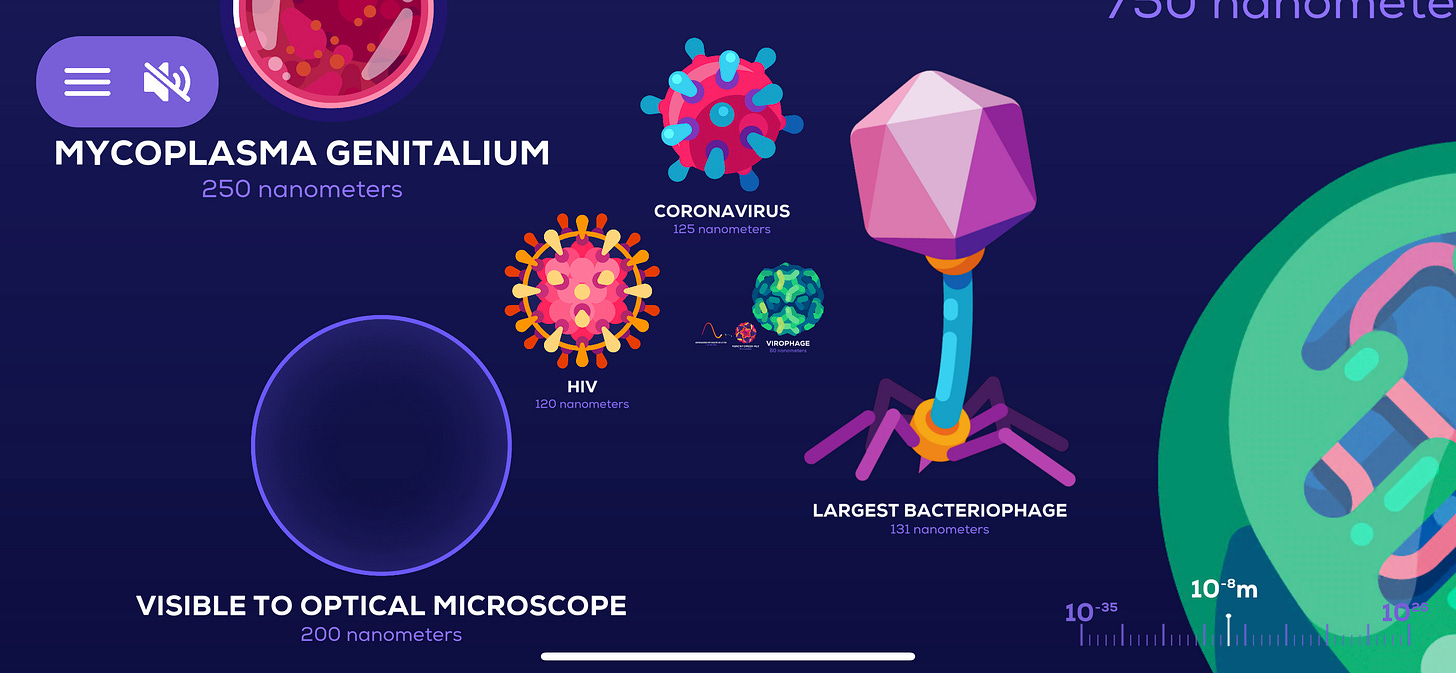

A micron is small, really small. It is 1/1000 of a millimetre. There are smaller measurements, for instance, a nanometer is 1/1000 of a micron. What this means is that if a particle is smaller than 5000 nanometers in diameter, scientists expect it to stay. The rest they expect to fall. The measles virus is 120-250 nanometers so we expect it to stay in the air.

What about SARS-CoV-2? How big is it? Well, I tried to find out. First to Wikipedia (via Google):

Then following that footnote:

Then following that footnote to this paper which did not have any measurement in it at all! So back to the next Google result which leads to this paper which says that it is about 100nm in diameter which cited this paper as a reference which, at long last, was an actual study that measured it as 60 to 140 nm.

Suffice it to say, I am confused. But reading further, the issue is not that there are viruses flowing out alone but that they are attached to other stuff. And the issue is how large that other stuff is. But interestingly, it wasn’t the size of the virus per se but the mode of assumed transmission — in this case, droplets — that caused scientists to conclude that the virus was large. That is, Covid is respiratory and so like respiratory viruses it spreads in large droplets so, therefore, it is large. This is some circular reasoning right there which is, frankly, quite disturbing. Especially when you would have thought that you could determine large versus small by just measuring the thing of interest.

Anyhow, whatever it is, the threshold between being an aerosol versus being a droplet is 5 microns. Smaller than that and aerosol transmission is considered possible. Larger than that and it is all about droplets.

But this Wired article documents that the 5-micron threshold is itself somewhat arbitrary and, by arbitrary, I mean “pulled out of thin air.” Instead, if you conducted actual studies that measured what stayed in the air and for how long, the threshold you would use would be more like 100 microns. That is a big, fat difference! For instance, all respiratory illnesses, including influenza would come under that threshold. Which would mean that the flu could be transmitted by aerosols which means that for decades infectious disease experts have misclassified it.

Given its importance, it is surely critical to understand where the 5-micron threshold came from in the first place. This paper tracks the history of “thought.” The WHO guidelines can be laboriously traced back to a TB scientist, William Wells (in 1962). But somewhat like my own rabbit hole trying to find out how big SARS-CoV-2 is, it turns out that Wells never mentioned anything like 5 microns. (Indeed, he seemed to conclude that a threshold like 100 microns was more appropriate.) Instead, it seems to have come from studies in the 1930s that suggested that only the smallest particles (< 5 microns) could reach the lungs. But that is very different from how they got to a person in the first place.

The point here is that if you are going to use a rule of thumb to make critical decisions during a pandemic, you want to know where that rule of thumb came from, if only to revisit the issue as new specific information arrives let alone make assumptions on numerous respiratory viruses for decades that were likely incorrect. It is very dangerous to continue to presume anything.

So, to recap:

For decades, with no accounting for history, infectious disease experts have concluded that 5 microns were the threshold for aerosol versus droplet transmission with all of the consequences that lead to mitigation strategies.

SARS-CoV-2 does not appear to be a “large” virus by comparison to measles or TB that are considered small viruses because they have aerosol transmission but it is about the same size as, H1N1 (80-120 nm) which was held to be transmitted by droplets so it was decided that the same applied to coronaviruses.

You should read this and say “well, Joshua is not an infectious disease expert. He’s an f**king economist” so how can I trust this? I absolutely agree. I am finding it hard to write.

But I am going to put it out there because I am confused and, at least on the 5-micron issue, there seems to be substantial support from experts on that point. (Here is a good FAQ about all of this). But I do think that if there is a threshold and it is based on the measurement of something that can and was measured, that a simple comparison might exist somewhere that drove a conclusion rather than putting it into the bucket of respiratory disease and basing all conclusions on that. That logic would be like some world leader saying “it’s just the flu.”

What does all this mean?

I think it means that the field of infectious diseases needs a root to branch scientific audit to determine what is known, who studied it and is it up to date. That isn’t much to ask.